“Unlike a photograph that records just a fraction of a second, a wall is akin to a photographic plate, produced through this long exposure over generations,” says the artist Vikram Divecha about his latest art work, Wall House.

“A wall is a material witness to people, cultures and tangible and intangible histories. Often when I explore buildings that are slated for demolition in the UAE, I encounter walls that so poignantly hold the imprints of time. I have been wanting to extract and preserve such walls for almost a decade now.”

Since Divecha presented his proposal for Wall House for the Art Here 2022 – Richard Mille Art Prize in November last year, the Dubai artist has been trying to get an ambitious, idiosyncratic project off the ground – a museum with hundreds of walls. The walls will be excised from buildings facing demolition from neighbourhoods across the world, selected by local researchers and communities.

“I am urging everyone to imagine a single address that holds hundreds of addresses from around the world,” Divecha says. “Visitors will walk through a timeline of contemporary civilisations – interior walls and exterior facade walls from homes, schools, bazaars and hundreds of forgotten addresses.

“Such a multicultural archive will deeply echo with the people of the UAE who often leave behind no records,” he continues. “The walls arriving to the UAE’s shores will invoke histories of movement, of ports that are open to people and ideas, and the deeper network of the UAE’s maritime history.”

:quality(70):focal(646x520:656x530)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/7DKVFUVTKJDORLREUD5HBUUSS4.jpg)

Divecha already has one wall in store. For his commission for the Richard Mille Prize, he convinced the Department of Culture and Tourism – Abu Dhabi to help him excise a wall from a house that was being knocked down on Hazza bin Zayed the First Street, near Burjeel Hospital. Divecha assembled a team that cut out a 3.5 metre by 3 metre interior section from the two-storey building.

The wall is now encased in a self-standing frame in a storage warehouse in Mina Zayed. The artist took me to see it in March – we picked a path through the enormous space in Divecha’s car, and then he flipped on the headlights to illuminate the object itself.

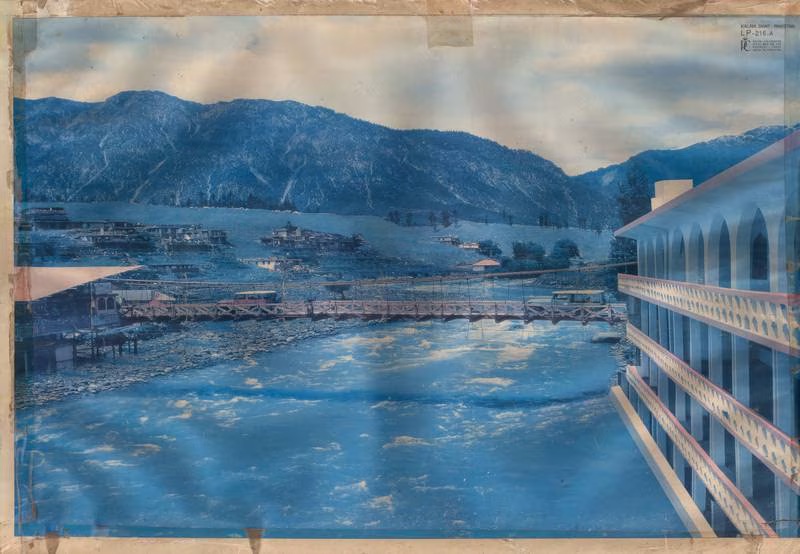

Grubby and beige, with a bold orange stripe along the bottom, its key feature is the posters that line its upper edge: faded tourist images from Pakistan’s Swat Valley, showing arched colonnades, elegant bridges and a gushing river. The pictures are themselves newly documentary: Divecha was told that some of these structures were washed away in the torrential floods in Pakistan of last year.

A run of cables and ethernet wires along the bottom of the wall shows what Divecha calls the “digital archaeology” of the site, or the apparatus by which the inhabitants of the flat would have called their family back home in Pakistan.

Though Divecha was unable to exhibit the work at Louvre Abu Dhabi (he showed a maquette of Wall House instead), he is hoping to bring it to NYU Abu Dhabi, where he teaches, as a social object of study – and a provocation, daring others to see it as more than just a two-dimensional relic, and ideally spreading the idea of Wall House even further.

Divecha is already speaking to communities in Kerala, where his wife’s family is from, to preserve a wall from a type of house called the tharavad.

“Tharavadsare large mansions that now stand as symbols of a matrilineal society, a system in Nair communities that came to an end almost a century ago,” he explains. “The property was passed down from mothers to daughters – and it was their identities that were associated with the tharavads, rather than their male partners or fathers.”

:quality(70):focal(2271x1047:2281x1057)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/F4I6W4TBEBBUHEGVUCIR5Y2NHI.jpg)

Many of the tharavads are now being razed down – but Wall House would be able to tell of the feminist practices they once contained.

This is all, of course, a guess. The tharavad wall might be just that: a wooden wall, slightly scratched, maybe a bit dilapidated. What stories can it really tell? But Divecha has always worked in offbeat, apparently logistical territory – unveiling aches and miseries of urban environments and creating space for new joys.

For his work Beej (seed in Hindi) at the 2017 Sharjah Biennial, he collaborated with the Sharjah government to transform a roundabout into an urban farm for the city’s Pakistani gardeners. The gardeners, who typically tended to the city’s roadside greenery, brought heirloom seeds from Pakistan – for tomatoes, turnips, spinach, mint and more – and had the chance to look after them in a garden-away-from-home.

For Road Markings (2017), he collaborated with the crew that maintains the white dividing lines and yellow arrows that orient Dubai drivers. The crew created stand-alone paintings comprised of these road markings that Divecha then hung at his Dubai gallery, Isabelle van den Eynde. The “paintings” became high-art – and in the process called attention to the starry crystals and patterns embedded in the roads, and the hidden labour that creates them.

:quality(70):focal(988x432:998x442)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/YWIDJ323NBDOTOV6IAPL2V5QXE.jpg)

Wall House also has a more specific precedent – a lesser-known project that Divecha did in 2013 called Reclaimed Void.

“I was given access to a factory in Dubai, and they showed me how precast panels for walls are made,” he says. “The way they would stack these panels was like pages, which allowed me to visualise these walls as pages of people’s lives holding intimate stories.”

His next step is to persuade donors to become a patron of a wall by funding their salvaging and transportation, perhaps from their home country. He has already found three supporters, he says.

“Wall House will eventually be shaped by the collaborators and supporters it finds. But it won’t just be a humongous sterile space with lots of walls in it,” he clarifies. “More than an architectural fragment I am interested in the wall as a social object. Researchers, artists and performers will build new communities around the walls. Through programming, education and performances the walls will be activated to bring their stories to life. And the more walls we have, the more stories we can tell in the future.

“I often wonder that all this sounds too far-fetched. But as an artist, one of my jobs is to imagine.”

Courtesy: thenationalnews