Matthew Fulco

Call it a comeback: Despite its agnosticism about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China is making diplomatic inroads in Europe from Berlin to Paris to Rome. It could not have been easier for Chinese leader Xi Jinping. All the Communist Party general secretary had to do was muzzle his “wolf-warrior” diplomats, whose overt jingoistic zeal had run its course, scrap the draconian “zero-COVID” policy and announce China was open for business again.

Though China’s truculence under Xi’s leadership has worn on Europe, a cold war between the two sides has been and will remain unlikely. After all, Brussels and Beijing do not compete ideologically or militarily like the US and China. Even the less-dire concept of decoupling has never resonated in Europe, which bristles at American-style confrontation with the largest importer of its goods.

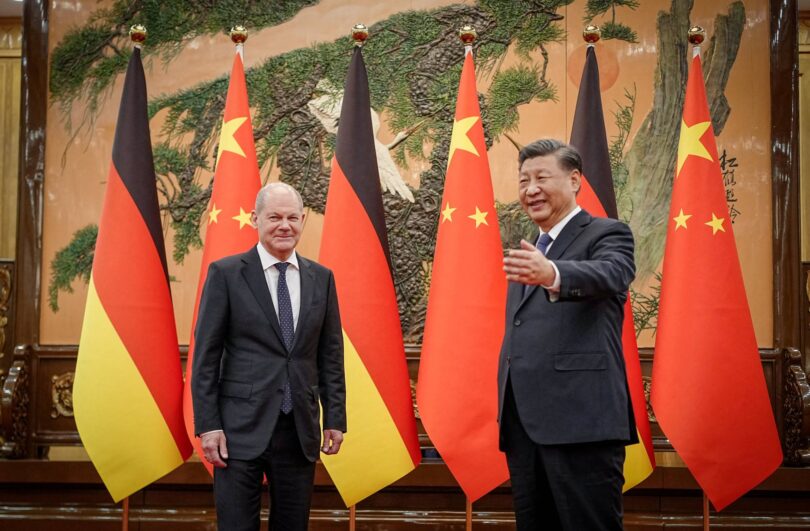

“China cannot be out, China must be in. This is the difference of view we have between the US and Europe,” French finance minister Bruno Le Maire said at Davos last month. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen had a slightly different take. Europe should “focus on de-risking rather than decoupling,” she said. For Germany, the de-risking bar has been set low. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz visited China in November with a heavyweight business delegation in tow, telegraphing to Xi that Berlin remains focused on commercial ties.

Scholz argued that he had secured a diplomatic win because Xi expressed his opposition to the use of nuclear weapons in the Russia-Ukraine war. In reality, China was the biggest winner. Xi managed to both please Scholz and avoid directly criticizing his close ally, Vladimir Putin. By calling on the international community to “reject the threat of nuclear weapons and advocate against a nuclear war to prevent a crisis on the Eurasian continent,” Xi reminded Putin not to cross the Rubicon – which would harm China’s interests – while reserving judgment about Moscow’s responsibility for the wider conflict. During his Beijing visit, the first by a European leader since Xi’s return to the world stage, Scholz told Chinese Premier Li Keqiang the two countries “were no friends of decoupling.” Data from Germany’s statistics office corroborate that claim: Trade between China and Germany expanded 21% annually in 2022 to €298 billion ($320 billion). Germany remains dependent on China for rare-earth metals used in the semiconductors, batteries and magnets of electric cars, an industry on which it has bet heavily.

German businesses, meanwhile, invested a record €10 billion in China in the first half of 2022. This money talks more clearly than German politicians calling for reducing their country’s dependency on China. French President Emmanuel Macron could be the second European leader to meet Xi after Scholz. Macron reportedly plans to visit China by April and discuss energy, trade and the Russia-Ukraine War. One can only hope the French president will have more success convincing Xi to mediate an end to the conflict than he did trying to persuade Putin not to instigate it. Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni could beat Macron to the punch. She has accepted an invitation to China that Xi extended to her when they met in Bali at APEC last November. Her agenda will be mostly commercial – she wants to boost Italian exports to China, Italy’s largest trading partner in Asia – while Xi’s will be more political. The Chinese leader told her at APEC that he hopes Rome will encourage the EU to pursue an “independent and positive” China policy.

While Meloni has previously been critical of China, voiced support for Taiwan and vowed not to renew Italy’s membership in Beijing’s embattled Belt and Road Initiative, she has moderated her tone since being elected as prime minister. In Central and Eastern Europe, China faces a less receptive audience. States that suffered behind the Iron Curtain, which have more skin in the game of the Russia-Ukraine war than Europe’s wealthy West, are aghast at Beijing’s refusal to condemn Moscow’s wanton aggression. Unencumbered by economic dependency on China, they are moving closer to the United States and in some cases Taiwan as well. China has tried to make an example out of Lithuania, killing the monkey to scare the chickens, as the Communist Party would say. To punish Lithuania for its overtures to Taiwan, which include allowing a de facto embassy with the name “Taiwanese Representative Office” to open in the capital of Vilnius, China has downgraded diplomatic ties and banned most imports from the tiny Baltic country.

Lithuania can shrug off Beijing’s pressure because their economic relationship is negligible. Vilnius has more to gain from greater trade with the US and Taiwan. To that end, it signed a $600 million export credit agreement with Washington in late 2021. In early 2022, Taiwan announced a $1 billion credit program that will fund joint projects with Lithuanian companies in six business categories. At the same time, China’s bullying of Lithuania has failed to sow disunity in the EU. Brussels has instead launched a World Trade Organization case against China and provided a €130 million support package for Vilnius. The Czech Republic looks like it will be the next domino to fall. Czech President-elect Petr Pavel spoke with Taiwan’s leader, Tsai Ing-wen, by telephone in January, prompting a harsh rebuke from China. “He has persisted in stepping on China’s red line, seriously interfering in China’s domestic affairs and hurting the feelings of the Chinese people,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning said in a statement.

Of the call, Czech Prime Minister Petr Fiala said in a statement, “As a sovereign country we decide ourselves who we have calls with and who we will meet.” China has yet to sanction Prague, though these are early days. This time Beijing may tread carefully though, cognizant that such bellicosity could backfire and destabilize its ties with the EU. For now, China is relying on coercive diplomacy.

Fu Cong, China’s EU ambassador, recently warned the bloc its growing engagement with Taiwan constituted a violation of the “One China” principle and is a “red line” for Beijing. Fu told the EU not to sign an investment agreement with Taiwan. The complexity of the endeavor, which would require unanimous approval from the bloc’s 27 members, means Beijing will get its way. Individual EU states will be harder for China to control, especially those most threatened by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. For these nations, standing up to authoritarian expansionism is a matter of survival – unlike Beijing’s deeply emotional but decidedly nonexistential obsession with Taiwan. By aligning with Moscow, China has made clear it stands with despotism. While the Beijing-Moscow axis does not sit well with Western Europe, the EU’s largest economies feel they must prioritize a stable relationship with Beijing to protect their commercial interests and they still hold out hope that China will help bring an end to the Russia-Ukraine war acceptable to Kiev and the West. That was always wishful thinking. At this point it seems closer to fantasy – especially after Fu told the EU that the “security concerns of both sides” in the war should be addressed.

The Japan Times