Hugh Tucker

Pulling in at the side of the road, I called the Salisbury Plain Training Area military hotline and a recorded message informed me that the roads to the ghost village of Imber were open. I drove on, passing through barriers that usually prevent access to the village. Blown-out tanks flanked the road, signs warned me of the threat of unexploded military debris, and what was once known as “the loneliest village in England” felt a world away from the idyllic towns I’d passed on my way here.

“Little Imber on the down, seven miles from any town”. As this old local rhyme demonstrates, the village was known for its remote location deep in a windswept valley in the rugged grasslands of Salisbury Plain, and this fostered the community spirit that allowed the villagers to survive the harsh winters on the plain.

However, its isolated location was ultimately the reason for its demise.

Imber has no inhabitants, no postcode and a maximum of 50 days of public access a year (Credit: Hugh Tucker)

Located in rural southern England, Salisbury Plain is now the largest military training area in the UK. Before World War Two, a 1,000-yard perimeter was respected when the army was training on the plain, but as more troops arrived and training ramped up in advance of D-Day, it was decided that the safety of the villagers could no longer be guaranteed. On 1 November 1943, the villagers were called to a meeting and informed that they had 47 days to leave.

Although some villagers begrudgingly accepted the news as a necessary sacrifice for the war effort, others were heartbroken. The day after the meeting, Albie Nash, the village blacksmith, was found slumped over his anvil, crying. Nash fell ill and passed away just a few weeks later.

After the war, it was announced that Imber would be retained for military training. The villagers, who said they’d been given assurances they’d be able to return, felt betrayed. A “Forever Imber” campaign succeeded in gaining public interest and the matter was raised in the House of Lords, but the decision that the training area would remain was deemed final.

Today, while Imber is still an active military training area, the village remains empty. It has no inhabitants, no postcode and a maximum of 50 days of public access a year, although, as Neil Skelton, the custodian of Imber’s 13th-Century St Giles Church told me, “I’m not aware that the full 50 days has ever been granted.”

The village’s restored 13th-Century St Giles Church continues to hold an annual Remembrance Day service (Credit: Neil Skelton)

Apart from the church, which has been restored, only the shells of a few original buildings remain due to damage from training and neglect. Despite this, Imber has no problem attracting visitors: pre-Covid, around 16,000 people visited each year to learn more about Imber’s strange history and explore one of the least-accessible villages in the UK.

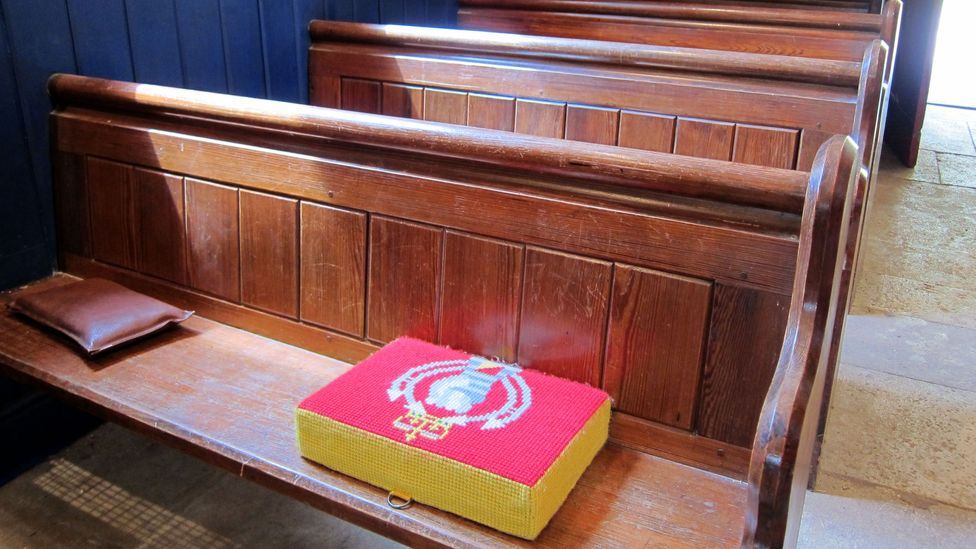

I travelled there on the first of four open days in early January 2023, and convoys of mud-spattered cars lined the road approaching the village. Activity centred around the St Giles Church, and the bells rang out while people tended graves in the churchyard and explored the medieval interior. The church continues to hold an annual service for Remembrance Day, and those who lived in Imber are still eligible to be buried in the churchyard.

We chose Imber because it was such an unlikely place to operate a bus service to

Imber’s story continues to evolve in unlikely ways. The idea for Imberbus – the village’s most popular open day – was born by chance in a Bath pub. Each summer, classic Routemaster buses ferry thousands of passengers across Salisbury Plain between the town of Warminster and Imber, raising a substantial amount of money for charity. Organiser, Lord Hendy of Richmond Hill, explained, “We chose Imber because it was such an unlikely place to operate a bus service to, and it represented a particular challenge as access is impossible for all but a few days a year… we’ve also made the village much more widely known.”

Imberbus is the village’s most popular open day and brings thousands of visitors to Imber (Credit: Lord Hendy)

Despite the demand, continued access to Imber isn’t guaranteed. Skelton explained that although the Ministry of Defence can grant up to 50 days of public access, they are only obligated to open one day each year, and, “about five years ago, as a result of trespass, the number of public access days was cut to three”. However, Skelton explained he was able to persuade the Salisbury Plain Training Area Commandant, the officer in charge of the area, to subsequently increase this to the current allocation of 12-plus days. For now, though, these access days allow thousands of people to discover Imber’s story and the relatives of Imber residents to retain a physical link with their past.

Please treat the church and houses with care. We have given up our homes where many of us lived for generations to help win the war to keep men free. We shall return one day and thank you for treating the village kindly

Imber wasn’t alone in becoming a ghost village in autumn 1943. Fifty miles to the south, on a stretch of coastline designated England’s only natural World Heritage Site, the car park at the village of Tyneham was full. Drivers waited for cars to leave, watching hopefully as dog walkers approached parked cars, and I looked out through my windscreen at the village that was brimming with people, despite also having a population of zero.

Tyneham was also evacuated in 1943 and residents were not allowed to return (Credit: BerndBrueggemann/Getty Images)

On 16 November 1943, an evacuation notice was issued to all households in Tyneham, an excerpt of which reads: “The Army must have an area of land particularly suited to their special needs and in which they can use live shells.” Chosen because of its small size and relative seclusion, residents of Tyneham were given just 28 days to leave. Although the notice didn’t state whether the evacuation was to be permanent, residents certainly believed they would be coming back. One of the last to leave pinned a note to the door of the church that read, “Please treat the church and houses with care. We have given up our homes where many of us lived for generations to help win the war to keep men free. We shall return one day and thank you for treating the village kindly.”

After World War Two ended, however, the government announced their decision to retain Tyneham as part of the Lulworth Ranges, a military area used by tanks and armoured vehicles for live-firing practice. A campaign to allow residents to return to the village was launched in the 1960s and a debate was held in Parliament, but the government’s decision to retain the area for military training was deemed final. Although the village wasn’t returned, limited public access was granted to Tyneham as well as footpaths across the firing area, and they are open most weekends and over certain holiday periods.

As I saw, there seems to be no shortage of people interested in visiting. A spokesperson from the Defence Infrastructure Organisation (DIO) that manages the site informed me that they estimate between 175,000 and 185,000 people visit Tyneham each year. And Lynda Price, who led the conservation and development of Tyneham from 1994 until her retirement in 2019, said that “the best way to describe it is an accidental tourist attraction”.

The tranquil church at Tyneham is a reminder of how the village once looked (Credit: Sabine Davis/Getty Images)

Walking into the village from the car park, I came to the cottages of Post Office Row and read the information boards sharing the stories of the people that lived there, like Gwendoline Driscoll who was the postmistress until the village was evacuated. While several ruined buildings were cordoned off behind metal fencing, exploring the schoolhouse, which looked like a lesson had just been interrupted, and sitting in the tranquillity of the church, it felt as though their occupants had recently been called away.

Roughly a mile from Tyneham, and still part of Lulworth Ranges, is Worbarrow Bay, where even in the cold January weather, several people were braving the water. Climbing a short way up the steep coast path above the bay, I looked back at Tyneham nestled in its valley, then towards the stunning coastline of this stretch of the Isle of Purbeck peninsula with its chalk cliffs, surrounding heathland and rolling hills. I was struck by how beautiful it must have been to live here.

It’s a tragedy that two communities that had survived for centuries were extinguished within the space of a month. But, while the residents of Imber and Tyneham can never call those villages home again, their use as military training areas and the consequent lack of development and settled human populations has meant that wildlife can thrive there.

The lack of development around Imber and Tyneham means that wildlife has been able to thrive (Credit: BerndBrueggemann/Getty Images)

Around Tyneham, there are many rare flowers, fungi and insects, including the Lulworth Skipper butterfly, which is only found on this stretch of coastline. However, as the DIO spokesperson informed me, “The real magic of Tyneham and other parts of the ranges is the mosaic of wildflower-rich grassland, ancient woodlands, mires and heaths that have largely escaped agricultural intensification as a direct result of being in Ministry of Defence ownership.”

The real magic of Tyneham and other parts of the ranges is the mosaic of wildflower-rich grassland, ancient woodlands, mires and heaths

Salisbury Plain also supports much noteworthy fauna and flora, including the Sainfoin bee that’s only found in Britain at a few sites in the Salisbury Plain area. “There are a myriad of rare, uncommon and protected species that thrive on the plain,” explained Dr Jemma Batten, the manager of the Plain Conservation project, “and for this reason, it qualifies as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, as Special Protection Area and a Special Area of Conservation.”

So, though people may no longer live at Tyneham or Imber, life continues.

Courtesy: bbc