PARIS (AFP): There is a popular saying that dopers are always one step ahead of the testers and while not a single case of genetic doping has yet been detected, authorities are increasingly vigilant.

Opinions are mixed as to whether genetic doping will take hold but it is taken seriously enough to have been included in the Olympic Bill which passed into law in France on April 12.

The law sets up the possibility that the laboratory of the French anti-doping agency (AFLD) will perform genetic testing at the 2024 Olympics in Paris, with the hope of being able to detect if genetic manipulation has taken place in a competitor’s body.

Genetic doping — which has been on the radar of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) since 2002 — is defined by using gene therapy for something other than it was intended for, namely introducing genetic material into the cells “in order to cure an illness”.

WADA’s science and medicine director Olivier Rabin does not believe genetic doping is simply pie in the sky born out of people’s fertile imaginations.

“I have tangible elements to make me think that it is not just theoretical,” he told AFP.

“Do we have proof of genetic doping among the athletes? The answer is no.

“There have been leads we have followed up on but which have only led us to classic doping products.”

Rabin, who joined WADA in 2002 and took on his present post in 2021, said it is only a question of time before those leads do uncover something.

“We see the arrival of products, created by ‘bio-hackers’ who are hugely interested in this genetic technique which they can produce in their garages.

“It is more affordable for the general public.

“We know that there are people who are performing these manipulations, and one day, that could very well be the athletes.”

The AFLD’s secretary general Jeremy Roubin is also convinced that genetic doping is a growing threat to clean sport.

“It is a proven threat, a real issue to watch,” he said.

“There has been an acceleration effect in recent years with practical implementations in gene therapy which have made these techniques more accessible.

“We can quite imagine that sports bodies wish to implement gene doping with the more or less explicit agreement of their athletes,” Roubin added.

However, Gerard Dine, a France-based professor of biotechnology, is sceptical about how cheap genetic doping would be to produce in practice.

“Gene therapy, as we understand it today, if you do not have the scientific or industrial infrastructure, for the moment you cannot do it.

“You are talking about billions of euros. Or you need to be a state-backed industry.”

Opinion is also divided over the effectiveness of the anti-doping tests — which the International Testing Agency (ITA) possess — in being able to detect genetic manipulation.

WADA’s Rabin believes they are reliable, but that view is not shared by Bruno Pitard, director of research at France’s National Research Centre (CNRS), who has worked in the field of genetics for 30 years.

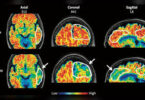

He points to the difficulties in detecting EPO, or erythropoetin, the blood-boosting substance that has been used by unscrupulous cyclists and runners.

“It is very difficult to distinguish, for example, the origin of the EPO signature. It is very tough to see if the EPO is produced by muscle or the kidneys,” Rabin said.

“It will be very difficult to detect (genetic doping).”