Monitoring Desk

After thousands of priceless artefacts were smashed by Taliban forces, the country’s National Museum is piecing the fragments back together and hopes to unveil them this year.

Located in the far south-western corner of Kabul, nestled between the distant snow-capped peaks of the Hindu Kush mountains and the broad Kabul River, the National Museum of Afghanistan stands as one of the world’s greatest testimonies of antiquity.

With a collection spanning 50,000 years from prehistoric relics to Islamic art, the museum highlights Afghanistan’s rich history at the crossroads of the ancient world. It has also survived decades of conflict – from Soviet occupation to civil wars to Taliban control – during its 89-year history.

“This country is rich with heritage sites and structures,” said museum director Fahim Rahimi, as he showed me around the hulking grey cement structure’s dimly lit first floor. But as I followed him up a staircase leading to the second floor, exhibits ranging from 4th-Century Greek art to Islamic artefacts from the Ghaznavid dynasty in the 12th Century AD revealed themselves. “This country [connected] Central Asia, South Asia and the Middle East. There was diversity here and these people [of different cultures] had [left] their legacies here.”

In each direction we had a different military group fighting one another, with the museum at the centre

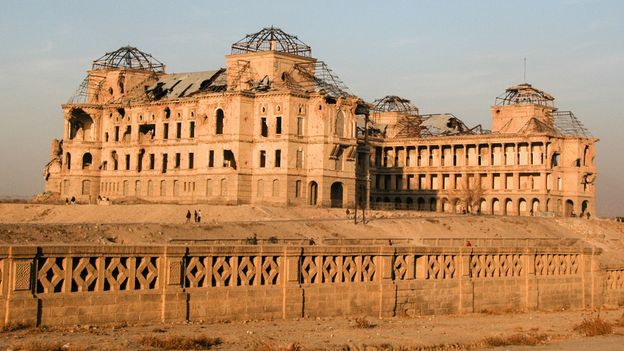

Yet, because of the collection’s immense value and the building’s location next to the city’s iconic Darul Aman royal palace, the museum and its artefacts have been repeatedly threatened, plundered or destroyed by the successive regimes that have fought to control the Afghan capital. Gold jewellery, weapons and coins from the 1st Century AD were hidden during the Soviet invasion in 1979. Following Soviet occupation in 1989, the museum was caught in the crossfire as various mujahideen guerrilla groups vied for power and control of Kabul in the early 1990s. In 1993, a rocket slammed into the museum’s roof, destroying a 4th-Century AD painting and burying much of its ancient pottery and bronzes. In 1997, a second rocket struck the building. And by the late 1990s, roughly 70% of the museum’s remaining artefacts had either been looted or destroyed.

“In each direction we had a different military group fighting one another, with the museum at the centre,” Rahimi said, speaking of the violence that swept Kabul during much of the 1990s. “Our museum staff could not protect the objects because it was impossible to even venture to these parts. It was during this time that we lost some of the objects.”

However, thanks to the heroism of the museum’s staff, a large number of the museum’s original collection had been secretly been removed and hidden during the Soviet-Afghan War that lasted from 1979-1989, and again later in the years just before Taliban rule – thus saving them from destruction.

According to Rahimi, during Soviet occupation, the museum’s curators convinced the communist-backed government to hide two-thirds of the museum’s collection in bank vaults and storage spaces inside the Ministry of Information and Culture in central Kabul to protect it from mujahideen attacks. Then, as various mujahideen groups fought over Kabul between 1992 and 1996, much of the museum was reduced to rubble and left without electricity or running water. But during a brief lull in the fighting, the museum’s staff (many of whom had been unpaid as the civil war raged) returned to the closed-down building in 1994 with kerosene lamps to fill some 500 trunks, crates and boxes with thousands of artefacts and secretly relocate them to the Kabul Hotel (now the Kabul Serena Hotel) for safekeeping.

When the Taliban seized control of Kabul in 1996, the fighting reduced, but the regime inflicted what is perhaps the greatest damage to the country’s ancient artefacts: destroying anything it deemed to be anti-Islamic. In an act of destruction that shocked the world in March 2001, Taliban commanders planted explosives in and around what were once the world’s tallest Buddha statues and blew up the 3,000-year-old sandstone structures in the country’s Bamiyan province. However, less known is the destruction that took place at the National Museum.

In February 2001, Taliban officials demanded to enter the museum’s vaults and began smashing anything in human or animal form that they believed was blasphemous to Islam with hammers and axes. These visits continued, and by the end, thousands of priceless objects dating back millennia had been destroyed.

“Over a period of a few weeks, the Taliban regularly came to the museum and smashed the many historical statues that we had on display and in the storerooms, including many Buddhist statues they deemed un-Islamic,” recalled a museum staff member who identified himself with the alias Mohammad Asif, as he believes he is still in danger for helping to rescue artefacts from the Taliban years ago.

Asif has worked with the museum for the last 40 years, with a short hiatus during the Soviet-Afghan War when he was forced to flee the country because mujahideen fighters believed he was a communist sympathiser. “When I returned to Afghanistan, there wasn’t much left of the museum. We tried to save the little that we could that survived the war, but eventually the Taliban came and destroyed those too,” he said.

Unable to stand by and watch the destruction of their country’s history, Asif and his colleagues gathered the broken and shattered artefacts left behind after each of the Taliban’s rampages and hid them around the museum. “Because of the efforts of our colleagues back then who saved these pieces [by] collecting [their broken parts], hiding them under the trash or in rooms where the Taliban wouldn’t look, we are now able to restore some of the history,” Rahimi acknowledged.

Today, the original collection that staff members saved has been on display since the museum’s reopening in 2004. And now, a small team of Afghan and international experts, led by conservator Fabio Colombo and supported by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, is working to restore many of the artefacts that Asif and the museum’s staff hid from Taliban fighters. The project, which is part of a larger partnership between the Institute and the National Museum supported by grants from the US State Department, is aiming to piece together some 2,500 Buddha statues and ceramics from the museum’s collection, focusing on Hadda, a bustling Buddhist hub that existed in Afghanistan some 2,500 years ago.

“The French first excavated [the collection of statues in Hadda] in the 1930s. Part of the findings were taken to France and the rest were on display in Kabul where they were eventually destroyed by the Taliban in 2001,” Asif said, showing me some of the more than 7,500 statue fragments spread across the many tables – some as tiny as grains – that experts are piecing back together in the museum’s back rooms. It took Colombo more than a year to evaluate and analyse the fragments in order to set a budget for the ambitious four-year project, which aims to culminate with an exhibition in the National Museum later this year.

According to Rahimi, the French excavated nearly 20,000 Buddha statues from Hadda, and in later years, Afghan archaeologists also recovered a substantial trove of other artefacts from the site. “We will never know the exact numbers because we don’t have the documentations of that, which were also lost during the [civil war and Taliban regime],” he said.

A few inventory documents from the 1960s and ‘70s were found in the museum basement and provide some visual direction to help experts piece the artefacts back together, though not much. “It’s like trying to assemble pieces from 30 different jigsaw puzzles that have all been dumped together without the pictures from the boxes,” said Colombo. Still, the team is determined to restore as many statutes as it can.

When completed, the Hadda artefacts on display in the National Museum will depict an important story of the Buddhist history of Afghanistan, a religion that held considerable influence in parts of Afghanistan’s Hindu Kush mountain range. “Buddhism came to Afghanistan in [the] 3rd Century BC, during the Ashoka period. And this was also the time we had a prevalent influence of the [Greek] Bactrian period, so you can find that fusion of the two cultures in the form of very elegant and beautiful statues you see in Hadda,” Rahimi explained.

Afghanistan is full of amazing pieces of history

However, for Colombo who has worked on various archaeological and historical restoration projects in Afghanistan since 2002, this initiative is about much more than just Hadda. “Afghanistan is full of amazing pieces of history, but we have a lot of problems with security threats,” he said. “This project is an opportunity for Afghans in the sector. I hope [it] will be the start of something else – a generation or two could be trained around this project. I am talking about conservators, archaeologists, art historians and even engineers and architects. There is so much to learn from this.”

Still, each member involved in the Hadda conservation project remains deeply concerned with the developing political situation around them. As the US administration negotiates an end to its 19-year-long conflict with the Taliban, the museum staff worry that there is a real possibility of the Taliban returning to power, and raises concerns over the militant group’s willingness to tolerate their efforts of historical conservation.

“We have a very glorious Islamic history that we are proud of, but we also have a rich pre-Islamic history [that] we must preserve,” Rahimi said. “It is important our youth learn about this history, this diversity and their heritage.”

Colombo remains hopeful. “There has been a lot of change in how people view history and [archaeology],” he said, adding that he hopes to train the next generation of Afghan cultural custodians to protect and preserve the country’s past. “A whole generation has not had [many] opportunities. We need a lot more to motivate the young generation and give them opportunities to pursue work in this area.”

Courtesy: BBC