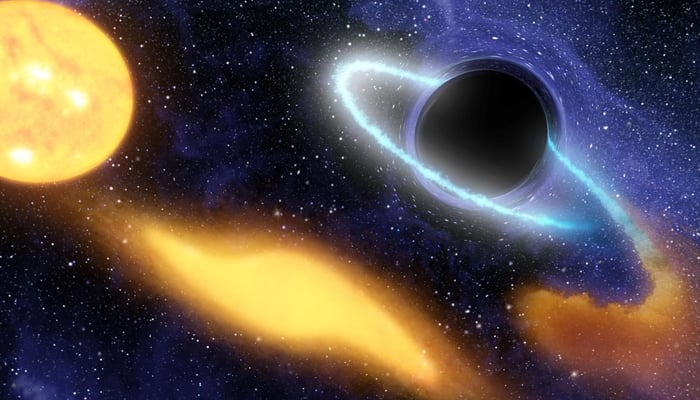

As scientists were conducting their observations in deep space, they detected for the first time a sound of gravitational waves — travelling all across space — which was formed after two black holes collided with each other.

According to astronomers, the ways travel at different frequencies for decades, making waves as they pass by our Milky Way galaxy. The new discovery may allow the experts to have more insights into merging galaxies and supermassive black holes.

The gravitational waves — initially predicted by the physics genius Albert Einstein in 1916 — are ripples in space-time that were first identified in 2015.

These were detected from the remaining stellar material such as pulsars — ejecting radio waves — from the exploded stars.

According to Einstein’s theory, gravitational waves would stretch and compress space as they moved across the universe, affecting how radio waves travel.

The observations were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The newly detected waves are the most powerful that carry million of times more energy compared to a singular event detected in recent years resulting from black holes or neutron star mergers.

The study coauthor Chiara Mingarelli, assistant professor of physics at Yale University, said: “It’s like a choir, with all these supermassive black hole pairs chiming in at different frequencies.”

“This is the first-ever evidence for the gravitational wave background. We’ve opened a new window of observation on the universe.”

The gravitational wave background is a kind of cosmic noise which is made up of ultra-low-frequency gravitational waves.

As their speed is similar to light, scientists estimated that the rise and fall of one of the waves could take years or decades to pass by due to the space-time ripple effect.

Another coauthor and astronomer Dr Scott Ransom, said: “As we keep listening, we’ll likely be able to pick out notes from the instruments playing in this cosmic orchestra.”

“Combining these gravitational-wave results with studies of galaxy structure and evolution will revolutionise our understanding of the history of our Universe.”

As scientists earlier believed that supermassive black holes would orbit each other forever and cannot come together to create a sound like this “we finally have strong evidence that many of these extremely massive and close binaries do exist,” coauthor Dr Luke Kelley, assistant adjunct professor of astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley, said.

“Once the two black holes get close enough to be seen by pulsar timing arrays, nothing can stop them from merging within just a few million years.”

“The gravitational wave background is about twice as loud as what I expected,” Mingarelli said.

“Our combined data will be much more powerful,” said study coauthor Stephen Taylor, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Vanderbilt University, adding that “we’re excited to discover what secrets they will reveal about our universe.”