Bronwyn Howell

Anxiety about a dystopian “future of work” caused by advances in artificial intelligence (AI) is the latest outbreak of a remarkably persistent meme with a very long history. Before rushing to panic, or intervening to minimize anticipated harms, it is helpful to pause, take a deep breath, and consider what we already know about the effects of technological change on labor markets, and how this might influence the current response.

First, human beings are terrible at predicting the future. While John Maynard Keynes may have had a lot to say about monetary policy, his 1930 predictions about technological unemployment arising from “our discovery of means of economising the use of labour outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labour” proved wide of the mark. Had he been correct, we would now be struggling with how to purposefully deploy all our newfound leisure time created by technological change rather than stressing about it taking away our jobs — not to mention working on average as many, if not more, hours per week as in 1930.

A more recent example of misleading forecasts comes in the form of autonomous vehicles. Heroic predictions in the early 2010s suggested that by the mid-2020s, truck driving would be consigned to the dustbin of history, alongside blacksmithing and other professions annihilated by the industrial revolution. Tesla CEO Elon Musk tweeted in 2016 that the company’s cars would be capable of a cross-country automated drive by “next year.” In 2019, he tweeted that “everyone with Tesla Full Self-Driving” would be able to do the same. Yet as 2022 dawns, it seems we are no nearer to ubiquitous autonomous vehicle nirvana than in 2012. Rather, the optimistic forecasts are now being downplayed, with one now suggesting that driverless vehicles will not be common and affordable until the 2050s or 2060s.

Second, we need to be aware of the manifest biases and fallacies that magnify the weight humans put on potential losses compared to potential future gains. As a result of these biases, humans often seek to preserve the status quo over pursuing activities that lead to future changes, even when the expected (but risky) gains from the latter may outweigh those of maintaining the status quo. The preference for the status quo, and neat narratives that oversimplify complex scenarios, can lead to overlooking (or ignoring) important information that is not consistent with the current generally accepted meme — illustrated, perhaps, in Musk’s continued optimism for autonomous vehicles despite the evidence leading to others downscaling their forecasts.

The first and second points together lead to the third important consideration: the importance of independently verified data over forecasts and opinion in determining the need for and appropriateness of policy interventions. And data is historical by nature. Pausing to collect it rather than rushing to respond is recommended.

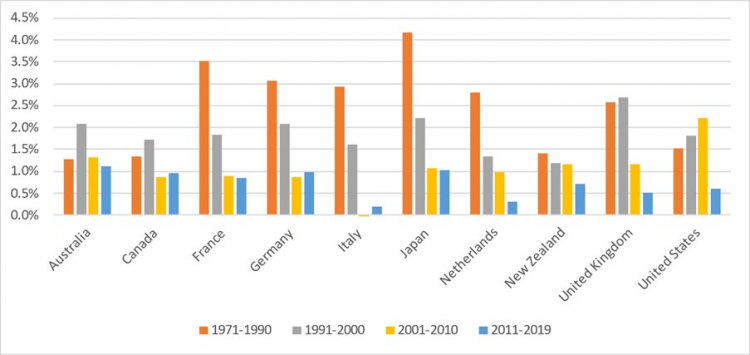

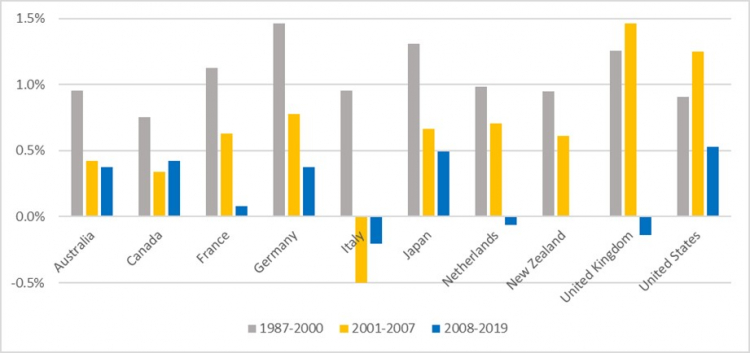

To that end, we can use available data to analyze whether increasing use of AI is demonstrably affecting key labor market performance indicators: labor productivity and multifactor productivity growth. If, as Keynes suggests, AI-driven technological change is increasing the potential for new means of economizing the use of labor to outrun the pace of finding new ways to use it, we would expect to see both statistics rising in the era dominated by AI. Yet as Figures 1 and 2 show, the exact opposite appears true for a wide range of OECD countries. Neither does the data suggest that other key labor market indicators have changed negatively with the advent of AI. As with the computer industry, we see the effects of AI everywhere but in the productivity statistics.

Figure 1. Labor productivity: average annual growth rates, selected OECD countries, 1971–2019

Figure 2. Multifactor productivity: average annual growth rates, selected OECD countries, 1985–2019

Indeed, the computer industry example provides perhaps a cogent explanation for these observations: the lump of labor fallacy. Proposed in 1891 by David Schloss, this is the misconception that both the amount of work to be done in an economy (and hence job supply) and the number of people who want work (and demand for jobs from workers) are inflexible. Yet the evidence shows this is far from the case. The introduction of spreadsheets dropped the price of running what-if accounting scenarios, and the demand for those scenarios was very responsive to price. Rather than decimating the market for accountants, spreadsheet software actually expanded it. The resources freed from calculating simple cases were deployed in accountants developing more complex scenarios to test.

The lesson from history is clear. While trying to get ahead of the game and protect workers’ interests is laudable, acting on predictions and pleadings rather than data risks harming the interests of those one seeks to protect.

Courtesy: (AEI.org)