Dan Storyev

The first emotion I felt when I found out that Navalny was killed was fear. That fear was also palpable among many activists I know, causing people to break down in tears – a chilling effect that reached all the way from the icy town of Kharp where Navalny died into the warm cafes of Tbilisi. But fear does not have to be paralyzing. Instead, it should push all of us into action.

The writer Viktor Pelevin once said that every Russian is subconsciously preparing for life in prison. This is especially true for Russian activists. We are afraid of police and phone calls from unknown numbers. We are afraid of late-night visits by masked agents. We are afraid of men in nondescript clothes passing us on a morning run. Ultimately, we are afraid of prison and death or injury at the hands of Putin’s state. There is much to be afraid of. There are over 1,000 political prisoners in Russia, and the country’s prisons are in themselves instruments of torture, a system inherited from Stalinist gulags. The treatment that befell Navalny is not unusual. Prisoners serve their terms in unbearable heat or cold, are thrown into punishment cells, isolated, starved, beaten and raped.

Everyone who opposes the Kremlin risks ending up in this inhumane system. Even those outside of Russia aren’t safe now that the Kremlin is ramping up transnational repression – just ask activist Lev Skoryakin, kidnapped in Kyrgyzstan, or Russian military defector Maxim Kuzminov, who was reportedly shot in Spain. Within Russia, even an American passport does not offer protection, as seen with the recent arrest of US-Russian dual national Ksenia Karelina, who faces up to 20 years in jail for a $50 donation to a Ukrainian charity. So the fear is well-founded. American science fiction writer Frank Herbert once wrote that fear is a mind-killer. But I always found this to be wrong. To me, fear has been a stimulus to grow smarter and stronger more quickly. Whether I was in Minsk in 2020, Moscow in 2021, or Izium in 2022, fear would push me and my colleagues to improve our operational security, wear flak jackets, and generally act with more care and competency.

Similarly, Russian activists use their fear to inform their tactics and strategies. They keep an emergency suitcase packed with everything they would need during their first days in prison, just in case. They use encrypted messaging apps and pseudonyms. Recently, most Russians have been picking protest methods that are less likely to land them in prison – shifting from mass street actions to more sustainable, covert tactics like sabotage and graffiti. The reminders of activists’ fears are woven into pop culture. The Russian rap-rock band Anacondaz begins their album “My Children Won’t Be Bored” with the words of a mother instructing her daughter to take an old phone with a “fresh SIM card” to a protest, along with milk and lemon juice to relieve the pain of tear gas. Of course, fear can also paralyze one into inaction, resulting in disillusion and apathy. To produce conscious action fear must be combined with hope, such as hope for a “beautiful Russia of the future” that Navalny always called for. This hope is the polar opposite of fear, but the two are still connected. Many Russians would define the “beautiful Russia of the future” as fundamentally free of fear, the fear of corrupt judges, drunk police officers, and the ever-present police state.

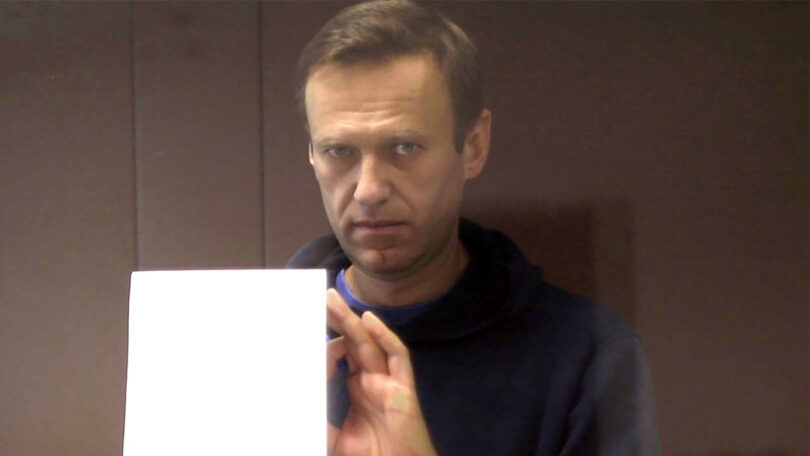

Hope might be a beautiful thing, but hope for a free Russia grew in the most gloomy conditions. Navalny’s fate is a testament to this. The last known video of the assassinated politician has him joking around, mocking the judge. His messages from the prison are bristling with sarcasm and pop-culture references. Navalny’s optimism carried him through the absurd and horrific tribulations that the Kremlin unleashed against him. And one of Navalny’s key messages was “don’t be afraid.” But what if we are afraid? We certainly should be. If you are in Russia, you should be terrified. If you are abroad you, too, should be worried. Putin’s nuclear-armed regime has kidnapped and killed dissidents beyond Russia’s borders. It is waging a war at the gates of Europe and becoming ever more emboldened. Soon, Putin will be re-anointed as Russia’s ruler after killing his main political opponent.

There are plenty of reasons to be afraid. That is why we should embrace fear, acknowledge it, and let it fuel our hope. We must understand that if we don’t want to live in fear, we need to strive for democratic change in Russia. Only a free Russia at peace with itself and its neighbors can rid the whole region of fear. To achieve this transformation, activists within Russia have to carry on Navalny’s legacy by building resistance to the Kremlin. And those in the West, whether policymakers or regular citizens, need to help Russian democracy, as they are well positioned to do so. They can write letters to Russian political prisoners, donate to NGOs and independent media, and make sure the world’s attention is on the Russian resistance.

We need to make sure that Navalny’s death does not go in vain. We cannot let fear paralyze us but stir us into action instead. We must ensure that the lives of political prisoners in exile are a key issue for Western foreign policy – while welcoming pro-democracy Russians who fled their country. That is how we all build the beautiful Russia of the future.

The Moscow Times