Kerry Boyd Anderson

The last three US presidents have all attempted to deprioritize the Middle East and focus foreign policy resources on East Asia. However, each one has struggled to shift away from the Middle East and the Hamas attack on Israel has once again demonstrated the challenges to US efforts to “pivot” to Asia.

In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the George W. Bush administration spent its two terms in office focused heavily on the Middle East. By the time Barack Obama became president in 2009, public support for the war in Iraq had declined. Obama criticized Bush for focusing on the war in Iraq at the expense of the war in Afghanistan and other US interests. Obama’s foreign policy team developed a strategy known as the “pivot to Asia.” Obama emphasized that “the United States is a Pacific power.” His administration understood that America was also a global power that still had substantial interests in the Middle East. The pivot to Asia was about rebalancing the focus of foreign policy to prioritize interests and concerns in Asia, not abandoning all interests in the Middle East. For example, the administration actively pursued sanctions against Iran and then used that leverage to negotiate limits on Iran’s nuclear program. Nonetheless, it was clear that the Obama administration hoped to reduce Washington’s focus on the Middle East.

Several major shifts in the region complicated Obama’s efforts to focus elsewhere. The so-called Arab Spring, the revolution in Libya, the civil war in Syria and the rise of Daesh all grabbed the foreign policy spotlight. Obama’s carefully crafted global and regional strategy was forced to adapt to realities on the ground. Donald Trump’s administration also emphasized a focus on East Asia, especially rivalry with China. Trump criticized the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and sought ways to reduce US military involvement in the region, including the controversial decision to withdraw troops from Kurdish-controlled areas in northern Syria. Trump pulled out of the nuclear deal with Iran and tried to delegate more responsibility to regional partners while reducing direct US involvement.

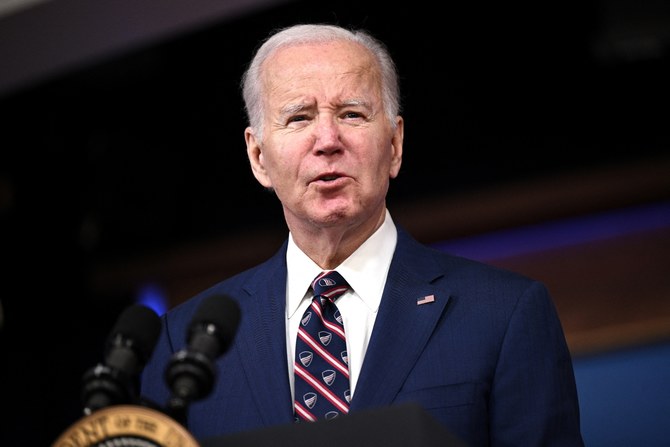

The Trump administration’s most proactive moves in the region were to pursue normalization agreements between Israel and several Arab countries, as well as a heavily pro-Israel approach to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. While Trump tried to focus on China and reduce the US footprint in the Middle East, regional developments and domestic political interests still directed foreign policy attention to the region. When Joe Biden took office in 2021, he followed Obama and Trump’s efforts to prioritize East Asia, especially given increasing tensions between Washington and Beijing. His administration deprioritized the Middle East, especially after attempted talks with Iran floundered. Biden administration officials were clear that they would not devote many resources to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Biden expressed strong support for Israel, restored aid to the Palestinians and sought to expand the Abraham Accords, but otherwise largely hoped to avoid extensive involvement in the region.

Then, Hamas launched its historic attack against Israel, igniting a new war in Gaza and increased violence in the West Bank. Just as previous administrations felt forced to react to the Arab Spring, the rise of Daesh and other regional developments, now Biden feels that it is necessary for the US to actively respond in a big way. The latest pull on Washington to pay attention to the Middle East highlights that US presidents can develop grand strategies with their preferred regional priorities, but there will always be events that undermine their ability to pursue their goals. Just as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to shifts in Biden’s foreign policy and a significant reallocation of resources, so the latest war in the Middle East disrupts efforts to pivot to Asia.

There is a sense among many in the US foreign policy community that events in the Middle East keep dragging Washington back to the region. Those who want a pivot to Asia find this frustrating. Those whose work focuses on the Middle East like to say, “I told you so.” Yet, it is reasonable to ask to what extent the US is forced to pay attention to the Middle East versus to what extent it chooses to do so. As a global power, America has strong strategic interests in the Middle East, given the region’s geostrategic position, the importance of oil and gas to the global economy, and concerns about nuclear weapons and terrorism that could threaten Americans. Furthermore, as China’s influence in the region grows, countering Beijing might require US action in the Middle East.

Other US priorities stem more from policymakers’ preferences and choices than from core national interests. In these cases, it is hardly fair to blame the Middle East for distracting the US from its interests in East Asia. America chose to invade Iraq in 2003 and then became entangled in the many consequences of that decision. The US chooses a strong alliance with Israel – and the many consequences – as much or more due to domestic political interests than pragmatic strategic concerns. It is difficult to distinguish between when the US must devote attention to the region and when it chooses to do so at a cost to other priorities. The Biden administration must now decide to what extent it should shift resources from other priorities to the Middle East in response to the latest war. Biden’s approach will say a lot to the world about his priorities and how he defines US interests.