Peter C. Earle

Throughout the late spring and summer of 2021, partially owing to pandemic policies and partially to hindered extraction, the price of palladium shot to over $3,000 per ounce. The average per ounce price of palladium between 2000 and 2018 was $509 per ounce; between 2018 and 2020, $1,288; and $2,342 between the start of 2020 and Friday, October 15th.

The rapid, profound price rise turned what had previously been an unusual, individual crime into an international effort undertaken by organized bands of catalytic converter harvesters. Teams trained to know the makes and models of cars having parts with the highest palladium content, and armed with proper tools and techniques, are sending streams of extracted emission control parts to underground salvagers worldwide.

AIER covered it at that time.

Palladium spot price USD/oz, 5 years (2016 – present)

It’s a crime that, understandably, falls hardest upon low-income vehicle owners. There have been less reports of this activity as the price of palladium has fallen back to $2,200 per ounce, but they persist.

In fact, policy-induced spikes and dips of commodities are cropping up everywhere. When they do, opportunists both amoral and immoral are never far off. In spring 2021, as lumber prices crested:

The Tennessee Department of Agriculture reports that rising lumber prices have caused an increase in timber thefts across the state…The department is urging landowners to take steps to protect their property…“We’ve had reports of oak trees, poplar, and some hickory stolen in Middle and East Tennessee,” [an] Agricultural Crime Unit Special Agent said[:] “One of the best ways to prevent this crime is to let your neighbors know if you will be removing timber from your property. If they haven’t heard from you and see harvesting, they should contact you or law enforcement immediately.”

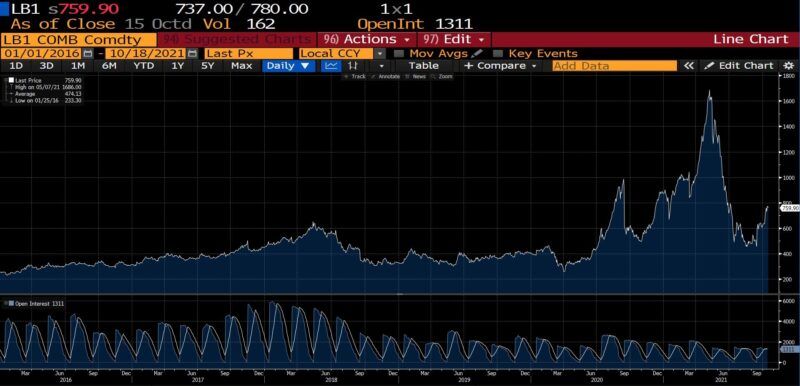

Lumber futures prices, 5 years (2016 – present)

And shortly thereafter, a lumber heist:

took place at Timber Creek Community, a neighborhood currently being built in Fort Myers, Florida. 144 sheets of plywood – valued at around $10,000 – were stolen on May 21…“Seven months ago, that was probably worth $1,500 and they probably wouldn’t want to steal it,” Precision Design owner and victim Kyle Arienta told Denver’s local CBS News.

As late as July, even as lumber prices were collapsing:

Several robberies have taken place in the Fort Worth area over the past few weeks. Thieves have even hit the same spot multiple times, taking a total of $42,000 worth of lumber. At one site, thieves sprayed “Thanks for the wood” as graffiti, reports Fox 4 News. Investigators told Fox that criminals are finding and removing hidden trackers placed inside the lumber before stealing…A group of home builders in Colorado says theft of lumber from job sites has reached levels never before seen. “Our explosion of job site theft over the past few months has been unprecedented,” said Renee Zentz, CEO of the Colorado Springs Housing and Building Association…The recent decline in softwood lumber prices hasn’t seemed to slow these thefts. Prices have dipped 40 percent since they peaked in May, but still remain elevated to what they were pre-pandemic.

In Canada, by one account, raiding thieves have gone so far as to hot-wire forklifts to load logs and planks into their own trucks.

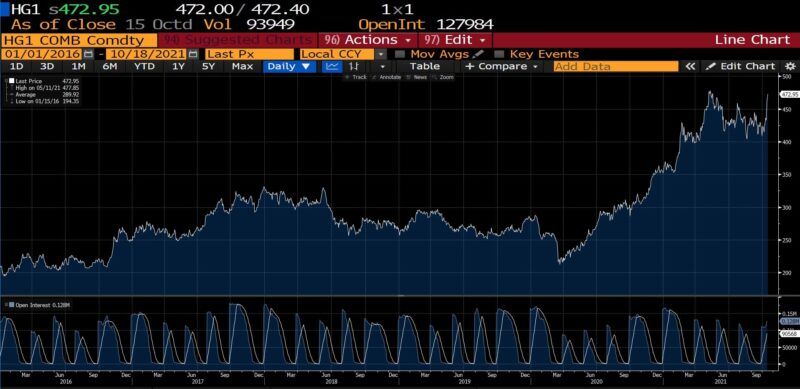

As the end of lockdowns neared and arrived, industrial concerns sought to acquire as much copper as possible, as quickly as possible, to capitalize on the global economic resurgence. Unsurprisingly, prices ran up 102% percent between mid-March 2020 and today. In Chile, as the price of copper rose heists have grown commensurately bold:

Thieves in trucks chase and try to intercept rail cars that depart from mines…They pilfer one or two bundles of copper cathode sheets at a time, each valued at 20 million pesos ($27,500). In March [2021] police apprehended three people near train tracks. In their truck they found tools strong enough to cut through the metal straps that fasten the copper slabs.

In perhaps the most brazen con, a trader undertaking the $40 million physical delivery of copper–a direct bet on a post-Covid industrial revival, or perhaps to hedge copper derivatives–received a truckload of painted rocks. (Bloomberg offers a literal illustration of the affair.)

Copper futures prices, 5 years (2016 – present)

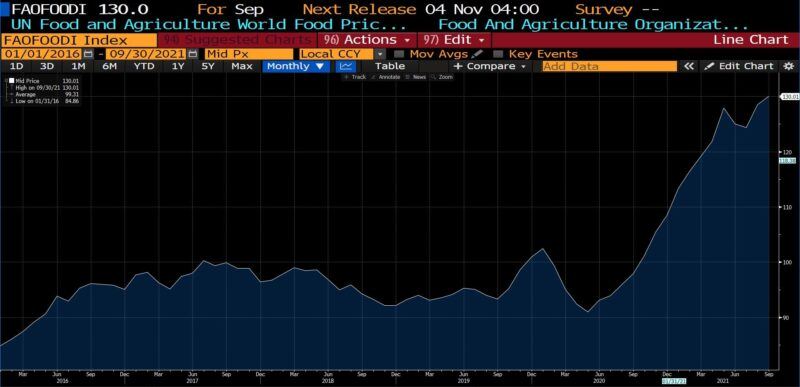

Elsewhere, food-related fraud and manipulation have increased in frequency as the prices of both raw and refined agricultural commodities have edged up. Food security was a concern as early as last spring; illicit adulteration exacerbates them.

United Nations World Food Price Index, 5 years (2016 – present)

Wrongdoing focused squarely upon the post-Covid commodity boom abounds. Driven to a large extent by central banking policy responses to the pandemic, other examples include a rash of home invasions targeting precious metals, technologically-enhanced cattle rustling, and industrial-scale oil siphoning.

Commodity Research Bureau Spot Raw Industrials Index, 5 years (2016 – present)

Willie Sutton is alleged to have said that he robbed banks because “that’s where the money is.” It’s a misattribution, but does explain why there were bursts of malfeasance during the dot-com era, during the inflation of the housing bubble, and have been throughout the rise of crypto.

Federal Reserve United States Money Supply M2, 5 years (2016 – present)

The allure of rapidly rising prices seizes interests ranging from the entrepreneurial to the gullible and the malign. Sometimes the inductive is intensifying competition, sometimes speculative fervor, sometimes bona fide shortages, and sometimes the effect of more and more money chasing the same or fewer goods and services. Usually a combination of the aforementioned is at work. It should not surprise that expansionary monetary policy, and in particular its effects on commodity prices, draw in seamy elements in rough proportion to the size of the increase, regardless of rationale and heedless of justification. The coincident tradeoffs of nonpharmaceutical interventions were apparent early on. The laggards now include mounting levels of fraud, theft, barratry, and violence. Unlikely though it is, hopefully that revelation will inform future policy choices.

Courtesy: (AIER)