Simon Urwin

“This is not a scenic drive,” said James Willcox, of adventure travel specialist Untamed Borders. “But what’s incredible about Route 1 is where it takes you: to the birthplace of some of the world’s earliest civilisations, the home of many of humankind’s greatest innovations.”

Willcox, who was charged with logistics and security for my journey, was briefing me before I embarked on a 530km, two-day road trip from Basra to Baghdad. My trip would be using Iraq’s first and longest freeway, the 1,200km-long Route 1, as a conduit to explore the heart of ancient Mesopotamia. Though the region has experienced decades of recent conflict, it was also once home to a series of illustrious historical empires (the Babylonians, Assyrians and Sumerians to name a few), and Willcox reassured me that the journey would be unforgettable so long as I followed some simple rules: “Keep a low profile, dress conservatively and don’t photograph any of the armed checkpoints,” he said.

I flew into Basra, Iraq’s largest port. The city straddles the Shatt al-Arab river, which is formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates – the two mighty waterways that inspired the name Mesopotamia (meaning “between two rivers” in Greek).

Fisherman Razaq Abu Haida lives along the Al-Ahwar wetlands, one of the world’s largest inland delta systems (Credit: Simon Urwin)

It was from Basra that the fictional mariner Sinbad the Sailor set out on his voyages to supernatural realms in Arabian Nights. By comparison, the start of my own journey was far more mundane. After I met my driver, we joined Route 1 on the outskirts of the city and spent the first two hours stuck in heavy traffic crossing desolate landscapes dotted with oil fields firing gas flares into the skies. But after 150km, the desert eventually turned to green as we veered off the highway and entered the vast wetlands of Al-Ahwar, or the Marshes. Regarded by some as the site of the Biblical Garden of Eden, these southern Iraqi marshes are one of the world’s largest inland delta systems, and have been slowly recovering since Saddam Hussein ordered them drained in the 1990s.

There, in the town of Chibayish, fisherman Razaq Abu Haida was waiting for me on the dock sporting a traditional black-and-white chequered keffiyeh headdress. He fired up the outboard motor and we puttered off together into the labyrinth of shallow lagoons lined with bulrushes and papyrus where the Ma’dan, or Marsh Arabs, have lived for more than 5,000 years.

Near a wallowing water buffalo, we pulled up at the mudhif (reed house) of the Alahwary family, one of just 25 families now living in the marshes near Chibayish. Razaq, the father, helped moor the boat while his wife, Naima, brought us drinks. “Milk, fresh from the udder,” she said, handing out cups of the warm, frothy liquid, complete with thick black buffalo hairs that had fallen into the urn. The couple told me they pass their days rearing buffalo, fishing for carp, baking bread over dung fires and scything reeds for housebuilding and thatching. Despite many people leaving for a more modern life in nearby towns such as Chibayish and Nasiriyah, they said they were happy with their simple existence, which had changed little since the Marsh Arabs settled the area and traded with the great city-states of the Sumerians.

The Sumerians were Mesopotamia’s earliest-known civilisation, credited with such inventions as the wheel, sail, plough, mathematics, hydraulic engineering and writing. According to Lanah Haddad, an archaeologist at TARII (The Academic Research Institute in Iraq), the Sumerians’ settling in the east of the Fertile Crescent was key to their success: the area’s rich soils not only provided people with plentiful food, which allowed them free time to innovate, but the region’s location between Africa, Asia and Europe enabled them to dominate world trade. “From 5,000 BCE up to the Mongol conquest in the 13th Century, this was the hub for the movement of all goods, and they became very rich and powerful as a result,” Haddad said.

A reproduction of the Ishtar Gate marks the entry point to the fabled city-state of Babylon (Credit: Simon Urwin)

Haddad also explained that unlike other civilisations, the Sumerians “didn’t destroy the achievements of those they had conquered”, but instead “respected their discoveries and improved upon them”. The Sumerians’ cuneiform writing system enabled them to record and share this knowledge, which, Haddad said “gave rise to the first, systematically collected and catalogued library in the ancient Middle East (the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal), and one of the earliest forms of written law: the Code of Hammurabi.”

The Code’s system of 282 laws arose during the reign of King Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE), who helped turn Babylon into Mesopotamia’s greatest city-state. From the Marshes, my driver and I rejoined Route 1 for the three-hour drive north-west to the ruins of this fabled city. Babylon became the largest city in the world under King Nebuchadnezzar II, who oversaw construction of its legendary Hanging Gardens (one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World), the Etemenanki ziggurat (popularly known as the Tower of Babel) and the Ishtar Gate, the modern-day entry point to the historic city.

Richly decorated with glazed-brick reliefs of dragons, oxen and chamomile flowers (an emblem of the Babylonian empire, believed to cure everything from wrinkles to male impotence), the gate’s foundations are original, while the upper part was taken away in the 19th Century to Berlin’s Pergamon Museum and eventually replaced with a garish reproduction as part of Hussein’s heavy-handed reconstruction of the site.

In the main part of the city, after mud bricks were discovered etched with Nebuchadnezzar’s name, the former dictator ordered new brick walls be built atop the 2,500-year-old foundations, bearing a message that read: “In the reign of the victorious Saddam Hussein… may God keep him the guardian of the great Iraq and the renovator of its renaissance and the builder of its great civilisation.” Hussein’s initials and image were also used to embellish a monolithic palace he built on a hilltop overlooking Babylon (one of 100 luxury residences he owned), with staff on standby around the clock in case he decided to spend the night. (He never did.)

The Shrine of Imam Hussain is one of the holiest sites among Shia Muslims (Credit: Simon Urwin)

My driver and I spent the evening in far less opulent circumstances, enjoying warm Iraqi hospitality and malfouf betinjan (meat-stuffed aubergine rolls, slow-cooked in tomato sauce) with our guesthouse owners. Awoken the next morning by the muezzin’s call to prayer, we set off early for the city of Karbala, 65km away.

Considered one of the holiest sites in Shia Islam, Karbala is home to the Shrine of Imam Hussain (grandson of the Prophet Muhammad), and that of his half-brother Abbas. These sacred sites attract up to 40 million pilgrims a year, and visiting them is believed to be of great spiritual benefit for both the living and the dead. (Both are accessible to non-Muslims.)

Inside the glittering prayer hall of Hussain’s shrine, I watched as a procession of pallbearers ferried coffins in and out to be blessed before internment, part of an organised burial trade known as “corpse traffic”. The business is said to have begun as early as the 16th Century, when Shiite corpses were carried by mule caravan from as far away as India and Iran in order to be buried in close proximity to these hallowed figures. Nowadays, the bodies come overland and by airplane before making their way to the cemetery of Karbala or Iraq’s other great shrine city, Najaf, which is 75km to the south and reached via a diversion along Route 8.

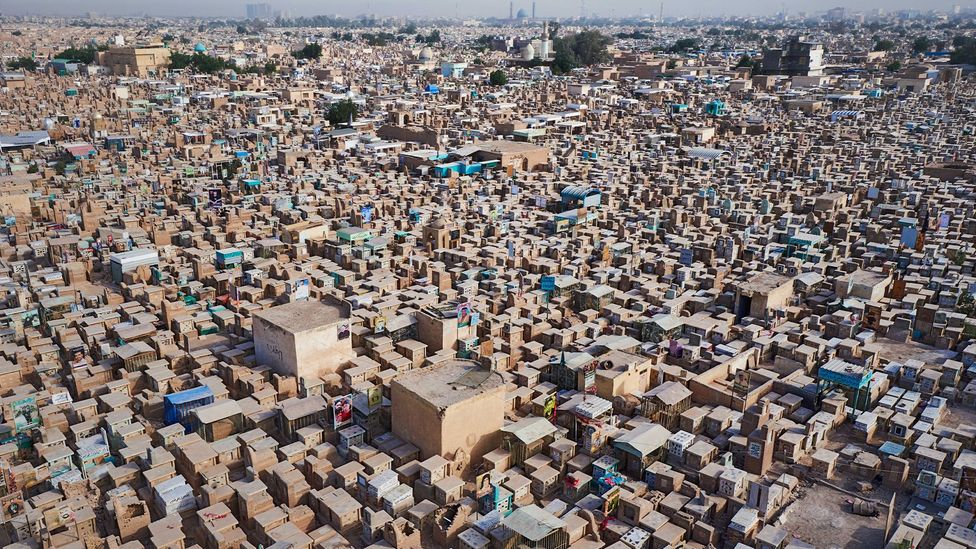

Established more than 1,400 years ago, Najaf’s Valley of Peace Cemetery has grown to become the largest in the world, the resting place of some six million bodies, the majority of whom are Shia Muslims. “The birds taught Muslims to bury the bodies, not cremate them,” said Karrar Ayad, one of 600 cemetery keepers who manage the site, as he repaired the stonework on a family crypt in the heart of the sprawling necropolis. “After Cain killed Abel, a bird used its wing to cover him with dust and stones.”

Najaf’s Valley of Peace Cemetery is the largest burial ground in the world (Credit: Simon Urwin)

Ayad also explained that after a burial, it is believed two angels descend to test the faith of the dead in their tombs; the righteous will go to heaven, but sinners are punished by the angels every day (except Fridays) until Allah deems otherwise.

Faced with such a potentially terrifying afterlife, I asked one family of cemetery visitors, who were washing a relative’s grave nearby with rosewater, if Shias typically feared death. “The rich do, only because they don’t want to let go of their possessions,” said Zainab Al-Hakim. “Maybe the poor desire it to escape their misery. But most of us don’t; we believe that your day is your day, whenever that may be.”

Leaving Najaf, we drove east for an hour to rejoin Route 1. After 160km, the dusty suburbs of the Iraqi capital came into view and we turned off towards its historic centre. Greeted by a sign that read, “Welcome to Baghdad, City of Peace”, we looped around the striking Martyr Monument, built to honour the fallen of the Iran-Iraq war, which stands rather incongruously next to the Sinbad Land Theme Park. By the shores of the River Tigris, we parked up in the old city, the heart of a once-great trading network whose caravan routes and maritime Silk Roads linked cities of the ancient world.

I wandered into the 1,000-year-old Al-Safafeer souq. The ancient coppersmith market takes its name, “safafeer” from the onomatopoeic word for a hammer tapping on copper – a sound that has dimmed in recent years. “Before, there were 126 craft shops, now no more than 16,” said fifth-generation coppersmith Amir Sayed Al-Saffar, as he crafted the handle onto a traditional coffee pot.

Al-Saffar is a fifth-generation coppersmith who works in a millennium-old souq (Credit: Simon Urwin)

Al-Saffar told me that Baghdad’s trade in intricate copperwares had dwindled as cheaper alternatives from China and India had flooded the marketplace. “It saddens me, but this has always been the way since the olden days,” he said. “New political and economic powers take over, one after the other. It is simply another page turning in the history book of Iraq.”

Al-Saffar’s words were a fitting end to my journey along Iraq’s illustrious Route 1. The mighty Mesopotamian empires the highway connects may have risen, fallen and ultimately turned to dust, but their milestone contributions to humankind still resonate across the centuries, and across the wider world, to this very day.

Courtesy: BBC