Jim Laurie

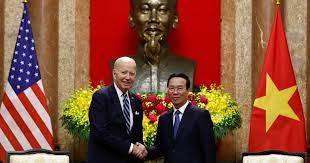

President Joe Biden returned here to Washington this week with his administration touting the success of his day-long stopover in Hanoi, Vietnam, after the G20 summit in New Delhi, India. Beyond a half-dozen investment agreements which provided business benefits for both sides, Biden came away hailing an announcement that the United States had established a “comprehensive strategic partnership” with the communist government of Vietnam – which Hanoi already has with China, Russia, India and South Korea.

He declared that the historic upgrade signalled that the US had “entered a new stage” in closer ties with Vietnam. Yet, while US-Vietnam relations are undoubtedly much-improved compared with some decades ago, Washington’s approach to Asia remains trapped in time. The result? It risks repeating past mistakes, with consequences for the US, Vietnam and the world. Biden was the fourth American President to visit Vietnam since the end of the war nearly 50 years ago. I accompanied the first. In November 2000, Bill Clinton flew to Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi to put an official stamp on post-war normalisation. For 20 years after America’s ignominious withdrawal from war-devastated Vietnam, successive US administrations insisted on punishing the victors with trade sanctions and rejections of normal diplomatic ties.

Clinton’s visit set the stage for 23 years of steadily improving relations. This latest visit was very different. It was less about Vietnam and more about Vietnam’s giant northern neighbour. If it weren’t for China, I suspect, Joe Biden wouldn’t have flown to Hanoi at all. When observing this latest American foray, one can’t escape the 70 years of history since the United States first became embroiled in the region after the Vietnamese bloodied the French and sent their colonial rule packing. Then, the US took under its wing the nascent South Vietnamese government of staunch anti-communist Ngo Dinh Diem: the first of America’s “Saigon puppets”, as Hanoi branded him. In those days of the 1950s, America found motivation in the menace of ‘Red China’ and more broadly the ‘communist threat’.

The Soviet Union’s Joseph Stalin had died in Moscow only recently, in 1953. Mao Zedong had taken the helm in Beijing in 1949. “The East is Red,” proclaimed Mao. The future was uncertain. Communism was on the march. From Hanoi to Jakarta, it was said, Southeast Asian nations would fall to communism like dominoes. Only the ‘preeminent power’ in the ‘free world’ could halt that shift. Seven decades later, the pre-eminent power is no longer fighting communism in proxy wars on battlefields in Asia. But similar language is still being used for what an increasing majority of members in the US Congress describe as a new Cold War. A Republican-led House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) says it is hard at work investigating how the CCP poses an “existential” threat to “fundamental freedoms” in the 21st century. What is really meant by such alarmist language is that China threatens America’s superpower status, that the world needs one superpower, and that moniker must remain attached to the United States. In March 2015, retired US diplomat and Harvard professor Robert Blackwill wrote a policy paper that has become an unofficial playbook for today’s American actions in Asia. It starts with a remarkable but unsurprising premise: “The United States has consistently pursued a grand strategy focused on acquiring and maintaining pre-eminent power over various rivals, first on the North American continent, then in the Western hemisphere, and finally globally.”

The Blackwell paper argues that the US must “protect its systemic primacy” and spells out how to do it in Asia. The paper maintains that China cannot be regarded as a “responsible stakeholder”. The CCP possesses its own “grand strategy” which seeks to “increase state control over Chinese society and, beyond its borders, to pacify its periphery, cement its status in the international system, and replace the United States as the most important power”. The US therefore must make sure China knows it can’t have free reign in Asia. The Biden administration is employing the 2015 Blackwell blueprint to the letter. That’s where Vietnam returns to strategic importance. Employing words like strategic competition, the US has returned to thwarting perceived Communist ambitions as it did so clumsily through war 70 years ago. Some questions are seldom asked in Washington.

Why should the United States be the sole superpower? Who appointed America the task of thwarting Chinese ambitions. Are those ambitions real? How much of the world wants continued US dominance? Would not more nuanced, multilateralist positions on international issues, and building a multi-polar world order be a greater guarantee of peace and stability? For insight into the American mind of the 21st century, it’s worth recalling a giant of US politics of the previous century, a figure now largely forgotten: Senator J William Fulbright. Fulbright experienced a conversion in 1965, emerging as one of the most eloquent opponents of the Vietnam War and America’s self-selected role as the world’s most prolific interventionist. He questioned the assumption that Blackwell and most Americans today accept – the idea of global preeminence. He wrote famously of America’s “arrogance of power”. “Power tends to confuse itself with virtue,” wrote Fulbright. “A great nation is particularly susceptible to the idea that its power is a sign of God’s favour, conferring upon it a special responsibility for other nations … to remake them, that is, in its own shining image.”

It was an attitude that permeated US actions in Vietnam; an attitude that Americans never unlearned despite repeated failures. The same ‘special responsibility’ came to be exercised again in Iraq in 2003 and throughout the 20 years that ended with another ignominious pullout – from Afghanistan in August 2021. The problem is that much of the world does not view the US as an unequivocal force for good. And many don’t share its view of China as an existential threat. Look no further than the recent BRICS summit in Johannesburg, which saw several nations – many of them US partners – queueing up to join the China-led economic bloc. Most of the world resists being drawn into a new cold war. They resist American alarmism. As Fulbright said so many years ago: “We all like telling people what to do, which is perfectly all right except that most people do not like being told what to do.” So again, America is attempting – as it is with other nations – to draw Vietnam into superpower politics. The good news for Vietnam is that it is strong enough now economically to resist being dragged on to one side or the other. It will maintain its careful balancing act, paying necessary obeisance to the Chinese with whom it must manage its territorial disputes while taking advantage of the benefits of a closer American relationship. Perhaps what the world needs is multiple “comprehensive strategic partnerships” like Hanoi has with several nations. Or in other words, true multilateralism.