Simon Tisdall

Like a proselytising lay minister naively intent on calming troubled waters, foreign secretary James Cleverly flew into Beijing this week on a whinge and a prayer. The whinge comprised a long list of British grievances, ranging from China’s attitude to Ukraine and Hong Kong to its spying on UK officials and sanctions on MPs.

Cleverly’s prayer was that his hosts would not realise that, when it comes to pursuing a coherent China policy based on deliberate, principled choices backed by political will and economic muscle, rudderless Britain is all at sea – but that Chinese leaders would kindly take notice of what he had to say anyway. If they did, they hid it well. Cleverly’s core message – “It’s better to talk than fight” – was not exactly gamechanging. After all, that’s the definition of diplomacy. As the Chinese played it polite and cool, it was plain that Tory hawks and cold warriors back home, shooting arrows at his back, were the ones who needed to hear the message most.

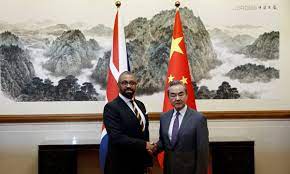

China’s emergence as a global leader is hugely challenging for all the western powers. But successive Tory governments have fumbled Britain’s response, blowing hot and cold, constantly sending mixed signals. Post-imperial Tories simply can’t agree what they want from a relationship in which they are not the dominant partner. Even as he stepped forward to meet China’s vice-president, Han Zheng, and foreign minister, Wang Yi, Cleverly was being accused of appeasement by hawkish colleagues. Meanwhile, parliament’s Tory-controlled foreign affairs select committee published a report, supposedly coincidentally, demanding a tougher line on China’s human rights abuses in Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Tibet, and a stronger commitment to defend Taiwan. In July, in a similar broadside, the intelligence and security committee said UK policy towards China had been characterised by short-termism and inconsistency. It’s hard to argue. David Cameron hailed a “golden era” and took President Xi Jinping down the pub. Boris Johnson slapped on sanctions over Hong Kong and banned Huawei. Liz Truss declared China a threat and called for an Asian Nato.

Now Rishi Sunak, ambiguity personified, flaps around terminologically, skipping from challenger and competitor to rival and threat, always watching what the Americans say, visibly torn between the claims of security and commerce. The galling bottom line is that the government wants it both ways – to stand up for “British values” while trading profitably – and as a result fails to advance either objective. Cleverly’s visit was less a fundamental relationship reset, more a change of battery in the remote. No surprise, then, when it fails to alter the bigger picture, or halt China’s most egregious abuses. This is hardly all his fault. The UK once had a reputation for skilled diplomacy: pragmatic, hard-headed, informed, clever, devious. But as its economic power and geopolitical leverage have diminished, along with the quality of decision-making, so too has traditional foreign policy realism. Now is the age of British foreign policy unrealism. Between fantasising post-Brexit Tories and the world as it truly is a huge, growing gap yawns.

The China conundrum perfectly illustrates this disconnect. It’s true Beijing deliberately tore up the Hong Kong joint declaration when it imposed direct rule. It’s equally true that ultimately UK lacked the will, as well as the physical means, either to stop or meaningfully punish it.

It’s true China commits terrible abuses in Xinjiang and Tibet. But it’s also true it knows the UK, huffing and puffing, will do next to nothing. Cleverly’s undemanding, conciliatory visit will reinforce that impression. The foreign affairs committee can demand as loudly as it likes that the UK treat Taiwan as an independent state. Yet calls for Britain to build Asia-Pacific alliances with India, Japan and others seem weirdly far-fetched. The reality is that if China decides to seize Taiwan by force, there will be precious little that faraway Britain, with its under-resourced armed forces, can or – crucially – will do about it, with or without allies.

Cleverly stressed the need to engage with China on the climate crisis. Sure, but not at the expense of other issues. Why believe a country that is the world’s biggest carbon emitter, and that is approving the equivalent of two new coal-fired plants a week, will take the slightest notice of British pressure? If China wants to cut carbon, it will, for its own hard-nosed reasons – not because that nice Mr Cleverly dropped in for a chat. The foreign secretary’s delayed Beijing trip comes some months after post-pandemic visits by Germany’s Olaf Scholz, France’s Emmanuel Macron, and the EU commission chief, Ursula von der Leyen. US secretary of state Antony Blinken was in Beijing recently, too. They all seek to influence a China whose behaviour appears ever more aggressive, authoritarian and threatening. It’s not easy. But the difference is that they are following, roughly, an agreed plan: it’s called “de-risking” the relationship. They work together, or at least try. Together they can apply leverage.

Not so, isolated, failing, ill-led “global Britain” which, vainly going it alone, up against a superpower, courts oblivion and oddball irrelevance. So there was Cleverly, all on his tod, under fire from hawks at home, lacking a joined-up strategy, spouting platitudes about dialogue, trying desperately to persuade the smirking Chinese to take him (and us) seriously. So sad. This politically illiterate, unilateralist international posturing is unreal. It’s un-realist. It’s humiliating for Britain, and it’s bound to fail.

The Guardian