John Harris

From leaked messages suggesting that Matt Hancock thought his job as health secretary was to “frighten the pants” off the public to Boris Johnson’s latest Trumpian contortions, our current political pantomime shows no signs of letting up. But underneath it all, something much more era-defining seems to be afoot: the British public’s two secular gods are taking a battering. The NHS is not in quite the mess it was a couple of months ago, but its deep problems grind on. Meanwhile, a slightly more overlooked story is becoming hard to ignore: a crisis in our national faith in property ownership, and the decline of that strange British belief that in any normal universe, house prices will only go up.

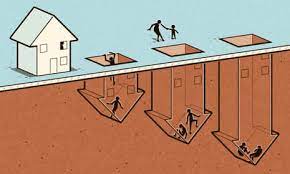

Figures released last week showed UK house prices were falling at the fastest annual rate since 2012, with warnings from the financial sector that “economic headwinds look set to remain relatively strong” and property owners reportedly having to cut their asking prices by an average of £14,000. To state the blindingly obvious, high interest rates are sucking demand out of the market by restricting access to mortgages. Houses and flats, therefore, sit unsold, and hundreds of thousands of people remain stranded in the purgatory between wanting – or, as politicians say, “aspiring” – to own a home, and being able to do so.

There is also a mind-boggling housing story rooted in the mad politics of the Conservative party. Late last year, as Tory backbenchers reached new heights of anxiety about losing their seats, the government was hit by the huge rebellion over local housebuilding targets, which became advisory rather than mandatory. The result is not exactly surprising: the Home Builders Federation is now predicting that rates of construction in England could soon fall to a low unseen since the second world war. Basic economics would suggest that this might send prices back up and make home ownership even more unattainable, but its impact threatens to be even more fundamental than that: as one Labour politician told me last week, one of the most absurd features of modern Britain is that “we’re not building houses in a housing crisis”.

The average British home now costs about nine times average earnings: one estimate I recently read reckoned that the last time UK houses were this expensive was in 1876. Three years ago, Legal & General found that 56% of first-time buyers aged under 35 needed a “financial gift” from their parents to buy a flat or house. Even if prices slowly fall, the old Tory vision of the property-owning democracy seems to have shrunk into a rigid oligarchy, built on very familiar foundations of class, age and wealth. There is, needless to say, no escape route into social housing. There are reckoned to be about 1.2m households on local waiting lists in England. Late last year, the Observer discovered that, thanks to post-2010 austerity, 40 local authority areas – including Peterborough, Luton, the Isle of Wight and parts of Greater Manchester – had neither built nor acquired any new social housing between 2016 and 2021. Across England, between 2021 and 2022, 21,600 social homes were either sold or demolished, but only 7,500 were built.

And so to the category of housing that seems to completely crystallise our problems. The private rented sector is what it has always been, only more so: a repository for people held back from either home ownership or social housing, where lives are often damaged by the rawest kind of business practices. Here, the arrival of comparatively punitive mortgage rates is pushing buy-to-let landlords to sell up and get out, which is forcing rents up even further. In Greater London, average advertised rent is just over 16% higher than it was a year ago; in Manchester, the figure is 20.5%. Studio flats – which older readers will know as bedsits – are unprecedently popular, and the fact that tenants have even less bargaining power is reflected in that very British sense of life as a private renter being all about broken heating, damp and the constant threat of eviction.

Where to find hope? There are signs that Labour has at least the beginnings of an answer. Lisa Nandy insists that she will be the first housing minister in decades to ensure that social housing provides for more people than the private rented sector; her mantra, she says, will be “council housing, council housing, council housing”. In the midst of impossible local authority budgets, she and her colleagues believe one quick solution to the housing crisis could lie in relationships between councils and pension funds. The idea would be for the funds to buy up discarded private rented property and then lease it back to local housing departments to renovate and convert into social homes. More thoroughgoing plans for building new social housing seem to be on the way, along with a new private renters’ charter.

The foreground of Labour policy, however, is all about home ownership. Not unreasonably, Keir Starmer sees buying a house as “the bedrock of security and aspiration”, and often makes glowing references to the pebble-dashed semi in which he grew up. Given the chance, he will apparently lead a government set on pursuing a 70% target for home ownership, up from England’s current figure of 64%. There is talk of a new mortgage guarantee scheme; the party’s first actions in government will include “helping first-time buyers on to the housing ladder and building more affordable homes by reforming planning rules”. Labour, we are told, “is the party of home ownership in Britain today”.

This is hardly outrageous: it is the kind of thing that politicians think they need to say to get elected. But I wonder if the gravity of the crisis we are faced with makes it sound increasingly hollow. One of the most basic human needs – for a secure and dependable home – is now way beyond the reach of millions of people, including many we might once have thought of as affluent. And even if access to the bank of Mum and Dad means you can just about afford to buy, isn’t the current reality of shoved-up interest rates and declining property prices a reminder of what that may well entail? Chasing security now means being at the mercy of its complete opposite: the hurly burly of financial markets, and fears of negative equity and repossession.

Recent(ish) history suggests there might be an alternative: council housing with lifelong, secure tenancies. Fifty or so years ago, thanks to investment by both Labour and Conservative governments, about a third of us lived in homes like that. This was not seen as proof of an over-powerful state, or people’s failure to stand on their own two feet: it was just a mundane and reassuring reality, and the foundation of millions of lives. If we are now a stroppy little island, full of a sense that precious things have been taken away from us, the deliberate decline of this way of living seems to me to be one of the key reasons. It is out there, waiting to be revived: if it was presented to the people currently locked out of the fading dream of property ownership, it might look like the basis of a very modern utopia.

The Gurdian