Keith Drew

It took me less than half an hour at Claudio Corallo’s chocolate factory in the sultry capital of São Tomé and Príncipe to realise that everything I’d ever known about chocolate was wrong.

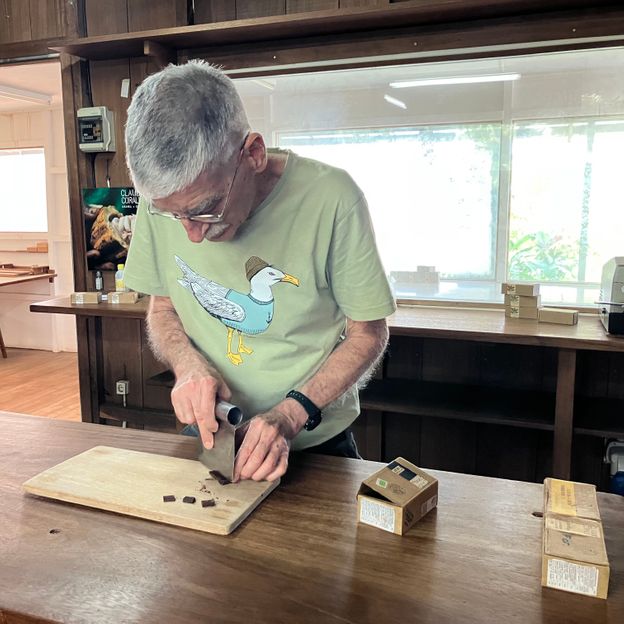

The 72-year-old Italian led me through a series of his creations, delicately carving slivers of chocolate onto a board and waiting for me to taste each one. As I slipped them onto my tongue, he watched me, head slightly cocked to one side, eyes twinkling through his glasses, waiting for the reaction he knew was coming.

His 100% cacao was strong but not bitter, and it mellowed the more I rolled it around inside my mouth. “Strong and bitter is not the same thing,” he said. “We are taught that good chocolate is dark and bitter, but bitter is wrong and dark is burnt.”

Among the array of concoctions I tried was Ubric 1, a 70% chocolate with raisins distilled in cacao pulp, the white gooey inside of the fruit described by Corallo as having “the freshest and most exciting aroma I know”. I’d never tasted anything like it. It’s no surprise that Italy’s Corriere della Sera newspaper has called him one of “the best chocolate makers in the world”.

Claudio Corallo uses cacao pulp – the white gooey inside of the fruit – in his chocolate-making process (Credit: Keith Drew)

Tiny São Tomé & Príncipe might be the second-smallest country in Africa, but little more than 100 years ago this twin-island nation was once the biggest producer of chocolate in the world. Now several local producers like Corallo are revitalising the trade, making use of age-old, untarnished cacao varieties, historic plantations and the country’s cacao-friendly climate to create organic chocolate products.

Corallo studied tropical agronomy in his native Florence – “I dreamt of rainforests as a child,” he told me – and grew coffee in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Zaire) for more than 30 years before moving to São Tomé and Príncipe when the political situation in Zaire deteriorated in the 1990s. Corallo wanted to use his coffee expertise to create a high-cacao chocolate that wasn’t bitter.

He found the cacao trees he was looking for at the Terreiro Velho plantation on the smaller, more pristine island of Príncipe, about 130km north-east of São Tomé, then set to work perfecting the process. Artisan chocolate-makers use different techniques during the key stages – harvesting, fermenting, drying and roasting – to create subtle distinctions in taste. Corallo’s approach combines time-consuming work with instinct.

Cacao is a living product, it wants to be known, [to be] treated right

He removes both the tegument (the woody shell that covers each bean) and its hard, bitter root by hand – very few chocolate makers bother to remove the root at all – and ferments the cacao for two to three times longer than is standard. Roasting, meanwhile, is done by accrued intuition. “Cacao is a living product, it wants to be known, [to be] treated right,” said Corallo. “To make great chocolate, you have to live in the feeling. If the temperature is too low and the roasting time too long, it takes away the happiness from the cacao. If temperatures are just a little too high or the time just a moment too short, they become bitter and sharp.”

Claudio Corallo has been described as one of “the best chocolate makers in the world” (Credit: Keith Drew)

The trees that grow on Corallo’s plantation are the descendants of the country’s very first cocoa trees. Up until the early 1800s, cacao had only been grown in Latin America. But King João VI of Portugal – recognising that he was about to lose Brazil as a colony and fearing the loss of income his court derived from Brazil’s cacao industry – ordered that cacao trees be shipped to Portugal’s more secure colony of São Tomé and Príncipe.

They arrived on Príncipe in 1819 and were quickly followed by enslaved people from West Africa and then indentured labourers from other Portuguese colonies, particularly Cape Verde, Angola and Mozambique, to work on the plantations that subsequently sprang up. The trees thrived in the rich volcanic soil, and by the early 1900s, São Tomé and Príncipe was the biggest exporter of cacao in the world, earning it the nickname of “The Chocolate Islands”.

The plantations, known as roças, were like self-sufficient towns, with a district of workers’ accommodations and their own church, hospital and schools. The living conditions of these indentured labourers was so poor, though, and their treatment by their landlords so brutal, that by 1910, British and German chocolate manufacturers had boycotted “Portuguese cocoa” and the local industry went into decline. The roças were abandoned altogether after São Tomé and Príncipe gained independence from Portugal in 1975, and they now lie in varying states of decay, their concrete skeletons slowly being consumed by jungle.

Roça Sundy is a former plantation complex repurposed as a boutique hotel (Credit: HBD Príncipe)

At Roça Sundy, once the second-largest plantation on Príncipe, the roots of ceiba trees climb down the walls of roofless warehouses. In an old storeroom, I found a battered manual dryer, a relic of the days when honeycombs of fermented cacao were laid out to dry atop huge wood-fed furnaces. One side of the roça’s central yard was lined by the crenellated facade of a medieval-looking stables, its weather-beaten clock stopped at half past seven. There were stretches of sunken railway track running through the roça and the derelict remains of a hospital.

The buildings might have seen better days, but life at Sundy continues. In the central yard, I watched scrawny cockerels scratch around in the dirt and giggling children chase piglets through the bushes. A lady swept the porch of a church that looked like it hadn’t seen a Sunday service in centuries. The plantation is home to some 300 people, descendants of the indentured labourers who originally worked here. They will be moving en masse at the end of the year to the Terra Promitada (the Promised Land), a newly built development with electricity and running water. For now, though, they still live in the sanzalas, the old workers’ quarters. It’s a vibrant community, despite the basic conditions.

Many of the men work in the plantation that tumbles away behind the yard and down to the sea beyond. “Under the Portuguese, this was all monocultures, with separate sections for cacao, coconuts and coffee,” said Jon McLea, agricultural director of HBD Príncipe, the ecotourism and agroforestry company that now owns Roça Sundy and has turned the old plantation owner’s house into a hotel. “But nature has run its own course over the last 50 years [since independence]. It’s been allowed to restore itself. So we are now involved in dynamic agroforestry, growing multiple species in a balance between cultivating cacao and preserving the forest.”

The Chocolate Factory at Roça Sundy makes small-batch bars that are sold across the islands (Credit: Keith Drew)

The hilly forest is now blanketed in a diverse tree canopy. Bananas provide shade for young cacao; coconut palms and flame-coloured coral trees act as an upper-storey layer of protection for the older, pod-bearing cacaos. Breadfruit trees are dotted among them all, their fallen fruit acting as a compost for the soil.

Cocoa beans from Roça Sundy used to be sold to a cooperative on São Tomé, which then exported them to Europe for processing. But in 2019, HBD opened the Chocolate Factory in a building in the roça’s central yard, where women from the sanzalas hand-sort the beans for small-batch bars to be sold on the islands. The chocolate is made under the Paciência Organic brand; Paciência was one of Roça Sundy’s satellite plantations at the height of the cacao industry and is now an organic farm run by HBD. (Both the Chocolate Factory and the farm are open to visitors.)

Lina Martins, the Chocolate Factory’s manager, guided me through the selection, which includes 60%, 70% and 80% cacao, and tied up bags of nibs, small pieces of roasted cacao beans. The 80% bar had delicate floral notes, despite its high percentage, while the nibs had an intense earthy nuttiness.

Cacao is like wine. If you rest a little between the stages, it tastes better

Martins makes just 150kg of each percentage every six weeks and waits for up to six months after fermenting the beans before roasting them. “Cacao is like wine,” she said. “If you rest a little between the stages, it tastes better.”

The plantation is home around 300 people, many of whom work in the plantation or at the Chocolate Factory (Credit: Scott Ramsay)

But this is good chocolate in more ways than one. “Cultivating rainforest-grown cacao into chocolate and other cacao-based products is one of the initiatives aligned with our vision for the sustainable social and economic development of Príncipe,” said Emma Tuzinkiewicz, HBD’s sustainability director. “We’re providing employment opportunities that are rooted in the natural richness of the island.”

HBD employs more than 500 people on Príncipe and built the new houses at Terra Prometida. By growing cacao beneath a rainforest canopy, they have also worked hard to keep their plantation as biodiverse as possible. “We know that our chocolate is only going to taste as good as the way we treat the Earth here,” said Tuzinkiewicz. “And it tastes really good.”

Courtesy: BBC