Robert F. Mulligan

The Federal Reserve System manages the US’s money supply, increasing or decreasing bank credit and other circulating media to reach a target interest rate usually announced at meetings of the Open Market Committee, which meets eight times a year. They met this week, announcing the first of several modest increases in the federal funds rate. To meet this target, the Fed will lower supplies of monetary aggregates until the federal funds rate reaches the desired target. This will primarily be accomplished by open market sales of US Treasury bonds, bills, and notes by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. In order to raise the interest rate, the New York Fed will sell Treasury securities to remove bank reserves from bank balance sheets, and this will have a leveraged effect because any lending based on those reserves will also be removed from circulating as part of the money supply. The greater scarcity of loanable funds held by banks will raise interest rates.

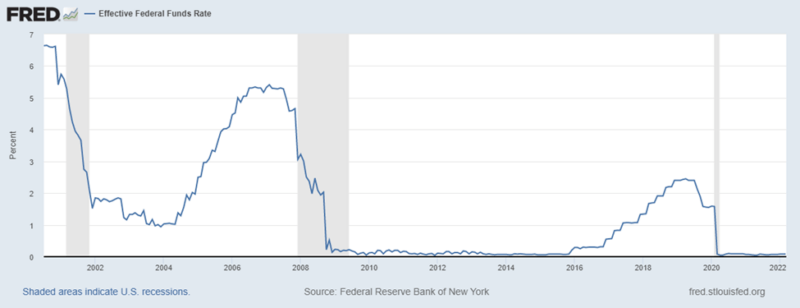

Figure 1: Effective Federal Funds Rate 2000-2022

Figure 1 shows this target interest rate was kept below 2 percent in the aftermath of the 2001 recession. This mild recession resulted from the bursting of the late 1990s technology bubble. Low interest rates in the 2000s triggered a new boom in real estate, construction, finance, and investments, including investments in highly-leveraged and non-transparent financial derivatives. Construction began to retrench as early as 2005, and the Fed realized the boom was not sustainable, so they tried to cool it down by raising interest rates. Unfortunately the overheated real estate and financial markets did not respond right away, and when they finally did, the result was the 2007 financial crisis and the 2007-2009 Great Recession.

The Fed responded by bloating its own balance sheet by purchasing worthless derivatives from distressed banks, paying inflated pre-crisis prices in order to bail out distressed banks, insurance companies, and brokerage houses. Successive rounds of quantitative easing—eventually the Treasury and the Fed either got tired of numbering them, or perhaps were embarrassed—kept interest rates near zero until 2017. Among other things, this easy credit policy reinflated real estate markets. The federal funds rate was only allowed to rise to 2.5 percent in late 2018. This would have signaled some attempt at a return to normalcy, but then COVID-19 hit, and the Fed quickly flooded financial markets with additional liquidity and bank reserves, keeping interest rates back at near zero levels. Rent moratoria and near-absolute shutdowns of restaurants, hospitality, travel, and manufacturing created an even greater loss of jobs and output than we saw during the Great Recession.

For the past few months the Fed has finally been facing the prospect of inflation. After increasing the money supply dramatically since the start of the Great Recession, we now have 7.5 percent consumer price index (CPI) inflation over 2021, accompanied by 24 percent broad producer price index (PPI) inflation—this suggests even higher CPI inflation in our future. Some industry-specific PPIs have increased even faster; for example, the PPI for metals and metal-producing industries increased an incredible 45 percent over 2021. These rather frightening figures indicate higher costs of production that will eventually be passed on to consumers.

Supply shocks like the turmoil in global energy markets due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine are not the result of loose monetary policy we can blame on the Fed, so while rising gasoline prices clearly contribute to further raising the CPI and the inflation rate, they are not the result of an expansionary monetary policy. Still, the Fed has much to atone for.

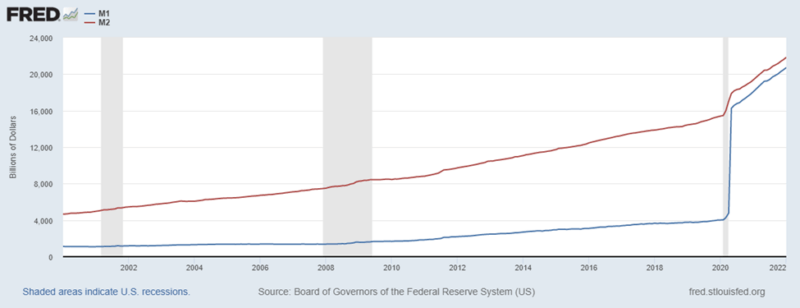

Figure 2: M1 and M2, 2000-2022

M1, or transactions money, consists of currency and coins in circulation, plus ordinary checkable deposits. These earn little or no interest, and can be spent without delay. M2, or savings money, is a broader measure of the money supply, and Figure 2 shows that until 2020, M2 was roughly four times the size of M1. M2 includes M1 but adds a number of interest-earning assets people typically use as savings assets. These assets are less liquid because they generally have to be converted to an M1 asset before they can be spent—transferred to cash or checking. Both M1 and M2 had been increasing steadily, and even at a moderately accelerating rate prior to the pandemic. This would have caused problems at some point, both in terms of inflation, and creating an unsustainable boom in investment that would eventually cause a recession.

Then the Fed responded to COVID-19 by further increasing M1 and M2. Although M2 only rose moderately, that sharp uptick in 2020 is still alarming and quite unprecedented in its own right. This is not a money supply that is being managed responsibly. The really remarkable event shown in Figure 2 is the virtual removal of traditional saving assets from the economy. These were things like savings account balances, money market mutual fund shares, certificates of deposit (CDs), etc. These were the differences between M1 and M2 and they used to account for up to 80 percent of M2. Since the pandemic, they only account for about 5 percent.

Why this happened is easy to understand in light of the near-zero interest rates these savings assets are currently paying. As long as savings accounts or CDs pay zero interest, there is little incentive not to keep that money in cash or checking. As the Fed starts raising interest rates, incentives will change, savings assets will become more attractive, and M1 should start to become a smaller fraction of M2. However, the Fed has managed to engineer a situation where prices are literally skyrocketing, while simultaneously supply constraints hobble any economic activity that hasn’t already been crippled by regulatory constraints.

It is never easy for policy makers to raise interest rates, but it is much easier for them to do that when the economy is overheating, prices are rising, and unemployment is low. Right now, we have a moribund economy with truly unspectacular economic growth. That would be bad enough, but it remains unclear how sustainable even this weak growth will turn out to be without serious structural reform. The one saving grace of our current situation is that unemployment remains low, but that fails to tell the whole story because our current low unemployment is due in part to unprecedented numbers of potential workers who are just not making themselves available in labor markets—the labor force participation rate has not been this low since 1977—though it is currently headed in the right direction. Low GDP growth and low unemployment rarely happen at the same time.

Each time the Fed raises interest rates, investment spending and investment borrowing will take a hit, and this may contribute to higher unemployment and lower labor force participation. Those outcomes will put pressure on the Fed to lower rates, or at least either delay raising them further, or raise them in smaller increments. If the Fed puts off raising rates to where they need to be for a healthy economy, inflation will get further out of control. With interest rates as low as they have been for most of the period following the Great Recession, the Fed really cannot squeeze out much short-run stimulus by lowering them further.

Over the months and years to come, it will be very interesting to see how faithfully the Fed pursues its policy of returning interest rates to normal and sustainable levels—approximately 3-4 percent for the federal funds rate. Every time the Open Market Committee meets for the next several years, they will face simultaneous pressure to lower interest rates to stimulate the economy and counteract higher borrowing costs, and pressure from other quarters to raise interest rates to fight inflation.

Courtesy: (AIER)