Dr. Amal Mudallahi

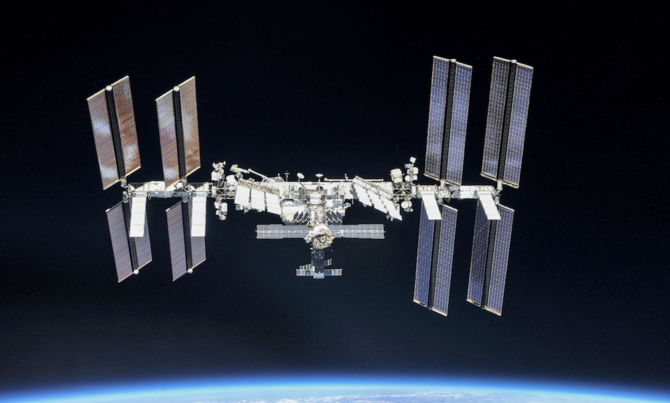

As Saudi astronauts were taking a “giant step” for the Kingdom and the Arab world by stepping into the International Space Station last week – inspiring the whole region, especially women, thanks to Rayyanah Barnawi becoming the first Arab woman in space – and joining their UAE colleague who was already on the ISS, I was listening to the first conference of its kind on “Preventing Space War,” sponsored by Arizona State University’s Interplanetary Initiative. It was unsettling to hear about war when the majority of the world is still taking its first steps in space, enthralled by its potential for all humanity.

The conference shed some much-needed light on what is happening in space, with different and divergent views of how various countries see space. Space today is a Wild West domain, with different powers vying for control and dominance. It is also a mess, with thousands of pieces of debris and discarded satellites, or space junk, circling in low Earth orbit, threatening astronauts on both the ISS and the Chinese space station, Tiangong. There is the potential for war to be sparked in space, as a result of a miscalculation or a misunderstanding, in the absence of transparency. All of this is happening at a time when space law, governance and space policies are either weak or entirely lacking.

The UN’s Outer Space Treaty of 1967 is outdated, with space technology light-years ahead of it, and the private sector’s big role in commercial space activity is unregulated. But most concerning is that big power competition and tensions are reaching space, mirroring the conflicts on Earth.

During the conference, US space officials and experts alike drew a picture of space that is contested, while expressing concerns about potential conflict if the domain remains without rules and if the current confrontations on Earth extend into space. Space forces are being created by different nations and the strategic picture of the new space era, in low Earth orbit and beyond, is as complicated and dangerous as it is on Earth.

The US sees the new era of space as one that is contested, but also vital to its national security and economic prosperity, as well as to space exploration and its ability to project power globally. China and Russia, meanwhile, accuse the US of “weaponizing” outer space. In a joint statement made by President Vladimir Putin and President Xi Jinping in 2022, they pointed to the US when they decried “attempts by some states to turn outer space into an arena of armed confrontation” and vowed to make “all necessary efforts to prevent the weaponization of outer space.” The US blames China and Russia for the debris in space because of their respective anti-satellite tests in 2007 and 2021. These two tests produced thousands of pieces of debris that are still circling in low Earth orbit, threatening space activity, the Americans complain. This prompted Lt. Gen. DeAnna Burt, the US Space Force’s deputy chief of operations, cyber and nuclear, to ask “where is my Greenpeace for space?”

The US last December led a process at the UN General Assembly and passed a resolution calling for a halt to one type of anti-satellite testing, with 155 countries voting in favor. China voted against the resolution and the Chinese military said the aim of the US step was to “strengthen themselves and weaken others,” because the “US military has already developed enough (anti-satellite) capability that no more testing was needed,” according to the South China Morning Post. Also in 2022, China denied “responsibility” for a rocket that slammed into the moon. Its Foreign Ministry said that China “conscientiously upholds the long-term sustainability of activities in outer space.” Space is getting too congested. There has been staggering growth in the number of satellites in space, up 500 percent since 2008, along with an increase in the number of launches and the payloads in orbit. According to Burt, the US has gone from tracking 13,000 objects in space to more than 45,000, including 2,700 pieces of debris from the Chinese test.

Both Russia and China, Burt said, “use space as a war-fighting domain and are developing sophisticated space capability intended to deny the US and our allies a space-enabled advantage.” China, she added, is “building outer space architecture to track and target US forces across all domains in order to fight and win a modern military conflict.” The Russians have, on the other hand, “demonstrated their belief that supremacy in space will be a decisive factor in winning future conflicts.” Burt said: “Space is more congested, more contested and includes increased competition from adversaries able to execute space-enabled attacks on our forces across air, land and sea.” She lamented the change in reality from when “space superiority was a given.” Today, the US “can no longer assume freedom of operations in orbit. A military service dedicated to maintaining space superiority is required.” The US Space Force was established in 2019 to maintain America’s superiority and enable it to continue to operate in space “in a time and place of our choosing,” according to Burt.

America’s strategy to maintain superiority in space was called “competitive endurance” by Burt. She said the US will continue to lead and show responsible behavior in space. While space experts highlighted the importance of communication and notification as key principles that reduce risk and prevent conflict in space, communication is currently missing from the Chinese-American relationship, whether on Earth or in space. Burt told the conference that the Chinese are not responsive to any US warnings about potential collisions in space, or even close encounters that could affect the Chinese space station. She said: “We get no response, no ‘thank you,’ no ‘have a nice day.’ Nothing.”

However, experts challenged the US argument about superiority in space. Christopher Johnson, space law adviser at the Secure World Foundation, questioned space superiority, calling it “illogical and not permissible under the Outer Space Treaty.” He said sovereignty “does not exist in space,” and “space is a shared domain.” He added that claiming dominance in a shared domain “builds to escalation, tension and anxiety akin to saber-rattling.” According to the Outer Space Treaty, countries should use “outer space for peaceful purposes,” but some experts thought that the treaty’s preamble was “aspirational,” when they were asked about the legality of placing weapons systems in space. Lt. Col. Matthew King, chief of international and administrative law for the Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said: “It is not prohibited under any law that I know.” Article IV of the Outer Space Treaty specifies only nuclear weapons and weapons of mass destruction, leaving a loophole. All participants agreed that international law and the principles of armed conflict apply in space.

One of the interesting issues discussed was whether a commercial asset should be considered a military asset if it is seen as such by an opponent, recalling the situation in Ukraine and the use of commercial satellites in the conflict there. While some agreed they are military assets, it was obvious there is an urgent need for a conversation about the role of the private sector in space, especially during conflict.

Burt spoke at length on the importance of having space law, norms and rules that govern behavior in space, saying that “having something is better than having nothing.” She said that, although the US has not ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, it follows it “customarily every day,” implying that the US might do the same in space. The Artemis Accords have their own norms, but they are adhered to only by the 24 signatory nations. She said that “there is no victory in space.” True, but there will not be peace either if no new or updated Outer Space Treaty is agreed to by all the states, especially the big powers. Amid the current tense relations between the US, China and Russia, preventing war in space will remain an aspiration. In his “Our Common Agenda,” UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called for a multistakeholder dialogue on outer space as part of his Summit of the Future this year. Time is of the essence for this conversation to start.