Fati N’zi Hassane

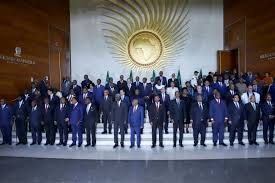

At this year’s African Union Summit held on 17-18 February in Addis Ababa, African leaders adopted the Nairobi Declaration on Climate Change – a powerful show of unity in the face of a real threat to Africa.

Alternating droughts and floods have withered or flushed away crops and decimated livestock. Hunger is sweeping across the continent. In East Africa alone, Oxfam calculated last year that 13 million animals, worth $7.4bn, and hundreds of thousands of hectares of crops were lost, leaving millions of people without income or food. Our water engineers warned that one in five water boreholes they dig now in East Africa is dry or has water unfit for people to drink without treatment. Too often, they must drill deeper, more expensive, and harder-to-maintain boreholes only to find dry, depleted, or polluted reservoirs.

Faced with the threat of climate change, the unity of African countries is increasingly evident in negotiating forums, and deserves to be applauded: the initiative to create a yearly African Climate Week, along with the involvement of the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment (AMCEN) and the African Group of Negotiators for COP, all under the leadership of the Committee of Heads of States and Governments on Climate Change (CAHOSCC), and with the Nairobi Declaration as the cornerstone of the a common African position, will create a robust mechanism to champion the interests of Africans.

The Nairobi Declaration’s assessment aligns significantly with civil society’s viewpoint, especially regarding Africa’s minimal historical contribution to global warming compared to the substantial burden of consequences affecting lives, livelihoods and economies. It is positive to note that the Declaration acknowledges the key role of local communities in climate action. However, we must ensure that we give these communities the resources and protection needed to cope with the effects of climate change. And this is exactly where the Nairobi Declaration falls short.

African countries committed to implementing policies, regulations and incentives aimed at attracting local, regional and global investment in “green growth”. The lack of clarity about what can be considered “green growth” opens the door to a myriad of solutions prioritising profit over people. For example, corporations can buy vast tracks of land to offset their carbon emissions abroad and continue pumping oil and gas – a reality sadly widespread in Africa and elsewhere – to the detriment of smallholder farmers and their environment. The call to rich countries to honour their commitment and scale up climate finance is an important ask, but it is necessary to look at the quality of the finance provided. While donors claim to have mobilised $83.3bn in 2020, Oxfam calculated that the real value of their spending was – at most – $24.5bn. The $83.3bn is an overestimate because it includes projects where the climate objective has been overstated or as loans cited at their face value. By providing loans rather than grants, these funds are even potentially harmful rather than helpful to local communities, as they add to the debt burdens of already heavily indebted countries.

Furthermore, the civil society organisations we work with often point to the lack of access and inclusion in existing climate finance mechanisms. In 2022, Oxfam found that only 0.8 percent of organisations that have direct access to international climate finance in the West Africa/Sahel region could be identified as “local”. There is still a lack of transparency in contributor reporting on how much climate finance reaches the local level and involves community participatory processes – this needs to change. It is necessary to create small grants that are both accessible and manageable for local populations. The Nairobi Declaration does not comprehensively address the multifaceted challenges faced by women. This is troubling. When food is scarce, women often eat least and last; and girls are the first to be pulled from school or married at a young age so there is one less mouth to feed. Many have to walk extra miles under the scorching sun, even carrying a child, to fill a jerry can of water, exposing themselves to safety issues. Resource stress exacerbates gender-based violence. A study on domestic violence in East Africa found that as the wealth status of women increases, the prevalence of domestic violence decreases, possibly due to fewer resource-related disputes.

The Declaration urges world leaders to establish a carbon tax on transport. But without adequate mitigation strategies, a global carbon tax could disproportionately impact the most vulnerable, further raising the costs of food, medicine and other essentials. What we need are investments that will truly reach and help people adapt to climate change so they can produce food. IFAD reports that in Africa, there are an estimated 33 million small-scale farms, producing around 70 percent of Africa’s food supply. Despite this, people in rural areas account for 90 percent of people living in poverty in sub-Saharan Africa according to FAO.

We also need investments in water and sanitation systems that will provide people with clean water and hygiene. In Southern Africa, only 61 percent of the population of SADC countries have access to drinking water, and only two out of five people have access to adequate sanitation. This is undoubtedly fuelling the recent spread of cholera in Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe where thousands of new cases and hundreds of deaths have been recorded since January. Africa stands at a decisive crossroads. By resisting quick fixes and deadly traps offered by the market and by bringing the people at the centre of the climate action, our leaders have a great opportunity to make a decisive step towards the Agenda 2063 aspiration of a “prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development”. It is by championing equitable access to resources and opportunities that we will build a continent where every individual not only survives but thrives in harmony with the natural world.