Razmig Bedirian

Anew exhibition at Louvre Abu Dhabi is diving into the genealogy of fables, tracing their parallel emergence in the eastern and western hemispheres and showing how they came together in the 17th century.

Bringing together more than 130 artworks, ranging from centuries-old manuscripts to contemporary works, the exhibition – From Kalila wa Dimna to La Fontaine: Travelling through Fables– opened on Tuesday and runs until July 21.

Louvre Abu Dhabi director Manuel Rabate says the exhibition fits with the museum’s universal mission and has been planned since before the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Fables are universal,” he says. “But also the mechanism of the diffusion and multiplication of these stories is very close to what we [strive to] show: the travelling of patterns, travelling of techniques, travelling of stories. It’s very much an echo of what Louvre Abu Dhabi is.”

Despite its universal appeal, the exhibition aims to ground itself within the local and regional context. “I think it’s a very dutiful exhibition and I’m glad that we are opening it during Ramadan,” Rabate adds. “It’s family-orientated but it also for adults. It’s an exhibition of curiosity.”

Passed down through generations in various cultures around the world, fables are a genre of literature that typically consist of short stories featuring animals or inanimate objects with humanlike qualities. These stories often convey moral lessons and teach readers about human behaviour through the actions and interactions of the characters.

The exhibition, being held in partnership with the national library of France and France Museums along with the support of Van Cleef & Arpels, begins by showing how the genre was used as an educative tool, for entertainment and for conveying political thought.

“It shows how fable traditions [were] born in parallel [within] the Oriental and the Western world, and how they gather together in the [works] of French fabulist Jean de La Fontaine,” says curator Annie Vernay Nouri. Fables, she adds, have long been used as an instruction to lead a life of “morality and ethics.”

The ancient Sanskrit collection of the Panchatantra is the foundation of the tradition that sprung up in the Middle East. Believed to have been written sometime between 200 BCE and 300 CE, it was feverishly translated across several languages. One of the earliest surviving translations was into Pahlavi in the mid-6th century. Two hundred years later, Ibn Al-Muqaffa wrote an Arabic version, adding his own twists and additions in Kalila wa Dimna.

By then, the Panchatantra was already ancient in its own right, but its popularity still surged. Ibn Al-Muqaffa’s Arabic work, however, would help propel fables towards new cultural frontiers.

Aesop’s Fables is believed to have been written in ancient Greece sometime between 620 and 564 BCE. It is at the root of the genre’s western tradition.

“There is a big difference in the form,” says Nouri, formerly chief curator of the Oriental manuscripts department at the national library of France. “Kalila wa DImna is like a Russian doll, with a story inside a story inside another story. In Aesop’s Fables and [the works of] La Fontaine, you have the fables [written] one after the other. There is no frame putting a link between them.”

The opening section of the exhibition shows how each of these traditions developed over time, moving from different translations with animals often being replaced to fit specific cultural contexts.

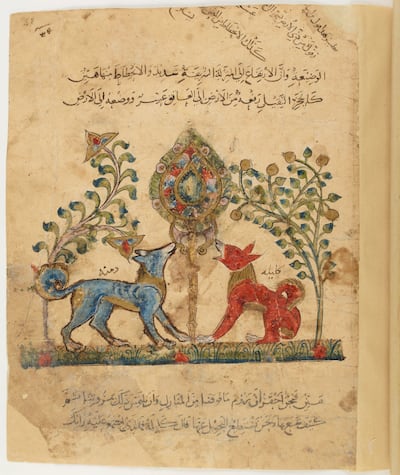

One of the most captivating pieces on display in this section is the oldest surviving illustrated copy of Kalila wa Dimna. Created in Syria or Egypt in 1222, during the Ayyubid Dynasty, it shows the influence of Byzantine paintings with drawn-out features of its characters.

Other translations of Kalila wa Dimna, meanwhile, underscore how the collection was tweaked to reflect its target audience. A Greek translation, for instance, renames its titular character as Stephanites and Ichnelates. In a 14th century Latin version, meanwhile, Kalila wa DImna, are rendered as rams instead of jackals.

Several historically-significant examples of Aesop’s Fables are also exhibited, including printed works produced in Italy and France in the 15th and 16th centuries that feature woodcut illustrations. The opening section also introduces the works of La Fontaine, showing how in the earlier phase of his career, he drew from the works of Aesop, before then finding inspiration in Kalila wa Dimna.

La Fontaine initially came across Ibn Al-Muqaffa’s writing through a French translation of a Persian translation of Kalila wa Dimna. These successive translations resulted in changes, sometimes dramatically enough so that only the moral of the story remained.

The second section exhibits these changes while also showing the commonalities of themes present across the works of Aesop, Ibn Al-Muqaffa and La Fontaine. Long banners hang over the space, segmenting the displayed artworks and manuscripts according to different morals. “Be content with what you have,” one advises. Others warn against “acting without thinking” or resorting to “trickery to win”.

The section dives deeper into the stories of Aesop, Ibn Al-Muqaffa, and La Fontaine, marking commonalities and differences.

The section also highlights a singular story that stands peculiarly as the sole meeting point between the Aesopic and eastern traditions. The Dog Who Drops His Prey For His Reflection is the only story shared between Aesop’s Fables and Kalila wa Dimna. It tells the story of a dog who drops his bone while leaping in an attempt to seize his reflection in the water.

The final section of the exhibitionbrings these age-old stories to the 21st century. Contemporary artworks from Egyptian, Turkish, Syrian and other artists show the lasting legacy of fables.

The exhibitionalso incorporates digital installations. There is a space where visitors are invited to lie down and watch animations projected on the ceiling.

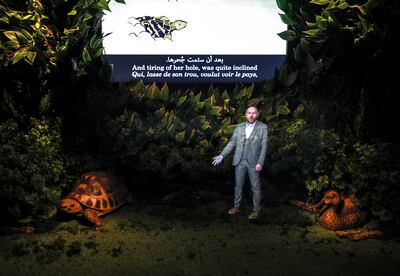

Another installation has a holographic component that tells the story of The Turtle and the Two Ducks. However, one of the most arresting comes at the very end of the exhibition and features a touchscreen where visitors can create their own fables using artificial intelligence.

Courtesy: thenationalnews