Brooke Newman

On 27 March 2007, nearly 450 years after Elizabeth I sponsored John Hawkins’ slaving expeditions to west Africa, Elizabeth II attended a service in Westminster Abbey to commemorate the bicentenary of Britain’s abolition of the slave trade. Rowan Williams, the archbishop of Canterbury, delivered a sermon focused on slavery’s “hideously persistent” legacies. “We, who are the heirs of the slave-owning and slave-trading nations of the past, have to face the fact that our historic prosperity was built in large part on this atrocity,” he said.

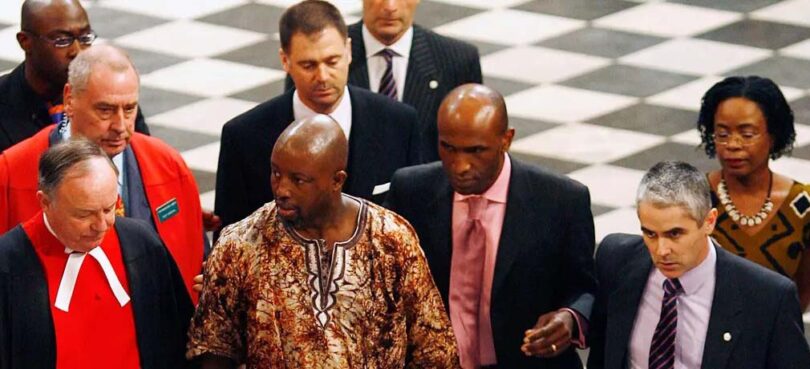

Moments later a Black protester dashed in front of the altar, disrupting the service with shouts of “This is an insult to us!” Her face impassive, Queen Elizabeth watched as security guards struggled with the protester, Toyin Agbetu, founder of the pan-African human rights organisation Ligali. As he was forcibly ejected, Agbetu pointed at the queen and yelled: “You, the queen, should be ashamed! You should say sorry!” In keeping with her own protocol and that of her namesake, Elizabeth I, whose motto was video et taceo (I see and keep silent), Queen Elizabeth said nothing. Outside Westminster Abbey, Agbetu told the press that an apology from the British monarchy was long overdue. “The queen has to say sorry. It was Elizabeth I. She commanded John Hawkins to take his ship,” he said. “The monarch and the government and the church are all in there patting themselves on the back.”

At the time, commentators overwhelmingly dismissed Agbetu as a “madman,” despite previous appeals for redress for the historical injustice of slavery. But the formal launch of the Caricom Reparation Commission in 2014, the Black Lives Matter protests that swept the UK in 2020 and mounting calls across the Caribbean to cut ties to the crown and push for reparations in the wake of the queen’s death offer stark evidence that Agbetu’s lone voice in Westminster Abbey was one of many. In fact, people of African origin and descent have demanded action and accountability from Britain and its monarchy for centuries. “The voice of our complaint,” the Black abolitionist Ottobah Cugoano warned the British public and George III in Thoughts and sentiments on the evil of slavery (1787), “ought to sound in your ears as the rolling waves around your circum-ambient shores; and if it is not harkened unto, it may yet arise with a louder voice, as the rolling thunder.” Mary Prince, the first Black woman to publish an account of her enslavement in Britain in 1831, agreed to share her harrowing life story to ensure “that good people in England might hear from a slave what a slave had felt and suffered”.

It’s rare for Britons, both then and now, to hear the voices of enslaved people. The transatlantic slave system that commodified its captives, transforming Africans and their descendants into human chattel, was not designed to preserve their experiences or perspectives. Its sole purpose was to generate profit for its operators. As the Kittitian-British novelist Caryl Phillips put it in The Atlantic Sound: “You were transported in a wooden vessel across a broad expanse of water to a place which rendered your tongue silent.” That compulsory silence extends to the archive of slavery. Although archives are full of stories, the voices they preserve are limited, fragmentary and far from neutral. They are, in most cases, the voices of enslavers, who continue to impart their outlook and version of events to future readers. “In history,” the Haitian scholar Michel-Rolph Trouillot observed, “power begins at the source.”

It begins in the surviving ledgers, ship manifests and stock books of slave-trading companies, in plantation account books cataloging births and deaths, and in the bound volumes of state correspondence between British officials and colonial administrators that line the shelves of archives. Through these manuscript materials, historians are granted access to the institutional records of the Atlantic slave system. But rarely to the enslaved themselves. The dehumanising horrors of slavery are replicated in the archive. “The objectification of the enslaved allowed authorities to reduce them to valued objects to be bought and sold, used to produce profit and to retain and bequeath wealth,” the historian Marisa Fuentes has argued. “This same objectification led to the violence in and of the archive.” The reduction of African people to commodities can be seen in the archival document I shared with the Guardian showing the 1689 transfer of £1,000 of shares in the slave-trading Royal African Company to King William III from Edward Colston, the company’s deputy governor.

To do justice to their subjects, historians of slavery must grapple with the problematic nature of the archive. However, the limitations of the archive do not explain why, as the coronation of Charles III nears, the British monarchy has not apologised for its historic links to slavery. The paper trail of crown involvement in slavery, though incomplete, is nonetheless extensive. As Saidiya Hartman noted in Lose Your Mother: “Money multiplied if fed human blood.” That British monarchs and members of the royal family invested in and profited from the slave trade and Atlantic slavery is indisputable. Still, if we hear anything about Britain’s or the British crown’s role in the enslavement and death of millions of Africans, the focus is almost always on abolition, not slavery. This deliberate rewriting of history, this purposeful forgetting, echoes a triumphalist narrative of national progress initiated more than 200 years ago by the famed abolitionist Thomas Clarkson. Popular support for abolition, he reflected in 1808, “overpowered me with joy. I rejoiced in it because it was a proof of the general good disposition of my countrymen.”

Passing legislation to abolish the slave trade in 1807 and then slavery itself in 1833 (after a period of forced “apprenticeship”), decades before the hard-fought victory of emancipation in the US, reshaped Britain’s collective memory. Its central role, and that of the monarchy’s, in the expansion of the transatlantic slave trade and horrors of Atlantic slavery was overwritten, replaced by a celebratory national history focused on the Christian conviction of Britain’s white abolitionist campaigners. Since 1807, Britain has told itself and the world that it is an abolitionist nation. An abolitionist nation that rejected human bondage, championing the rights of formerly enslaved people and their descendants as equal subjects of the crown. According to this national narrative, though slavery, in the words of Prince Albert in 1840, represented “the blackest stain on civilised Europe”, it was Britain that led the way toward its eradication.

But this version of British history is nothing but a muddled, self-congratulatory national myth, one no less misleading and historically dubious than the myth of American exceptionalism. The history of Atlantic slavery is equally a British story and an American story. They are separate yet interdependent strands of the same sordid tale; we cannot fully understand one without the other. “Those of us living in the rich societies of the west have all, albeit profoundly unequally, enjoyed the fruits of racial capitalism,” stressed historian Catherine Hall, head of UCL’s Legacies of British Slavery project; “we are all survivors of slavery, not just those who can directly trace their lineages.”

Evidence of royal involvement in what the UN has labelled “the greatest crime against humanity” committed in the modern era saturates the archive of slavery. King Charles has for the first time signalled his support for research into the monarchy’s historical links with transatlantic slavery. But more should be done to listen and respond to the descendants of the enslaved.

The Guardian