Razmig Bedirian

Vantage Point Sharjah has honed its focus for its 11th run.

The annual exhibition by the Sharjah Art Foundation is running until January 14 at the Old Al Diwan Al Amiri in Al Hamriyah. The event is usually known to host dozens of photographers. This year, however, it is instead presenting the works of four photographers and one collective.

This decision expands the breadth of work presented by each participating artist and gives room for the images and their processes to interweave in a way that wouldn’t have been possible with a larger pool.

Each photographer has an individual exhibition. There is also a communal area that puts their work in conversation, highlighting similarities in their photographic approaches.

While their work varies in style and subject, the exhibiting artists share commonalities in their experimental approach, and the way they repurpose found or inherited photographs or offer visual explorations of post-colonialism.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/4SP3IXRDQNHI3EA6X6MKFK24HI.jpg)

Oumaima Abaraghe’s work, for instance, responds to the fragmentation and inaccessibility of Morocco’s colonial archive. The Casablanca-born artist crops a wide range of historical photographs in her series, History as they present it reflects, arranging them in strips and obscuring their original subjects. In Heffi ainek, she refashions these archival photographs as silhouettes on translucent paper, underscoring the difficulty of articulating Moroccan history through the archives.

In the works Fkhater Idoudi and The Salted locust still leaps, meanwhile, Abaraghe pays tribute to oral family histories and nursery rhymes that contain traces of the trauma that Morocco has undergone during sequential droughts and famines. She takes dozens of photographs that exhibit the exploitation the country suffered during its colonial period and blends them with family photographs. The process is a testament to the role personal narratives have in challenging the fragmented state of colonial archives.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/DGIUEVERDND7XGL3336X5T5T7I.jpg)

For Mohamed Mahdy, being a documentary photographer isn’t just about depicting subjects, but also about providing them with an avenue of expression. He features overlooked communities in Egypt in his work, most of whom are marginalised as the country strives towards modernisation.

In Here, The Doors Don’t Know Me, Mahdy highlights the fishing communities in the Al Maks neighbourhood of Alexandria. The community is disintegrating in the face of the city’s redevelopment and is under the threat of mass eviction. He juxtaposes family photographs with images that show the destroyed homes and strewn belongings of the neighbourhood.

It is a chilling contrast of a community in its heyday and its contemporary, dilapidated state. The works also feature handwritten letters and poems from community members as they express feelings of nostalgia and uncertainty.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/QHMZSHZPBNA2DL7ALB7P2IXVOQ.jpg)

Yashna Kaul’s practice springs from a trove of family photographs she discovered in her family home in India. She manipulates the images using analogue and digital techniques to explore how we construct and inform personal histories. She also uses this approach to examine her father’s early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Kaul’s father is the prime subject of her Hands of God series. Using fragmented frames, she obscures family photographs so that the images are focused on his hands, and the large rings that adorn them, amplifying his presence while highlighting his faith in Vedic gemmology, an aspect of his character that has remained distinct in her memory of him.

She uses similar obscuring and framing techniques in System of Objects. The series, using opaque overlays focuses on female figurines that she noticed are motifs throughout family photographs. Their placement and decorative function changed as her polygamous father moved houses, and Kaul uses them as a vehicle to reflect on how personal objects are used a performative facet of identity.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/RHTVT6L3KNBCZH3OZZ5ZVQAK3E.jpg)

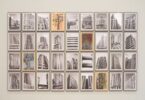

The collective Postbox Ghana, meanwhile, takes on postcard visuals from Ghana’s post-independence era and recontextualises them within the country’s current urban landscape.

The collective is made up of Nana Ofosu Adjei, Courage Dzidula Kpodo and Manuela Nebuloni.

Their work highlights how architecture was a medium for Ghana to express its newfound identity. Some of the buildings, however, did not end up serving their intended functions, and as the exhibition details, they “remained frozen through time – mute witnesses to military coups and economic downturns.”

One of these structures is a silo commissioned by Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president. The collective used the silo as an exhibition space, where they displayed archival images taken from postcards made between the 1950s and 1970s. The images were strewn in the water and mud that flood the floor of the silo today. A video of the project is displayed as part of their exhibition, a mesmerising and poignant study of state-building.

In The Beautyful Ones, on the other hand, the group planted archival images of Accra’s Makola Market within the area as it exists today, on walls typically reserved for advertisements. The collective returned to the photographs months later to record how they had changed over time, whether through public interaction or natural causes. Like with the preceding work, it is a powerful documentation of societal transformation.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/7FNT23SYZFC4HNSYKJ74BH3BGM.jpg)

In Monsieur, Clea Rekhou documents the men in France’s sole rehabilitation centre designed for those who have committed domestic violence. Rekhou, who was born in Paris and now lives in Algiers, visited the centre with the aim of exploring the spaces these men occupy as they try to reintegrate into society and become better people. The portraits, composed of cool hues, are filled with longing and regret.

The series, On the Edge, follows one of the men as he returns to his family after spending time at the centre. The images in the series highlight the many tragic ripples of domestic violence, as Rekhou focuses on family members and the trauma they endured.