Douglas Murray

Irecently caught up on an excellent documentary about the American withdrawal from Saigon. It’s as gripping and horrifying a subject as ever, but today it has a certain added piquancy. Because, of course, history never is history. Anyone who thought America might have learnt a lesson from that debacle will now have in mind the perhaps worse withdrawal from Afghanistan two summers ago.

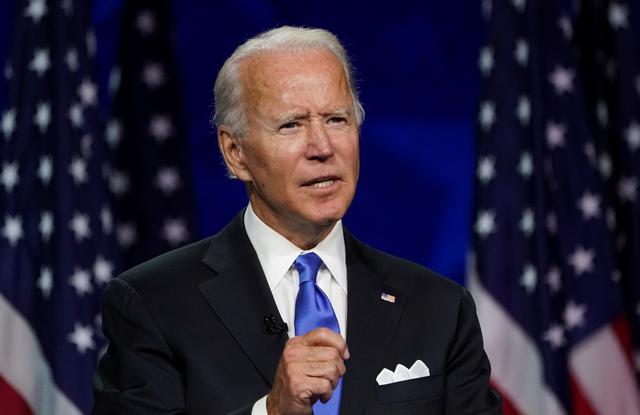

The similarities are uncanny. The panic. The desperate locals clinging to the last flights out. US troops in the embassy in 1975 were ordered to burn millions of dollars in cash so that the North Vietnamese wouldn’t get hold of it. That seems a bargain by comparison with 2021, when the Americans handed to the Taliban one of the most expensive and complete sets of military equipment in the world. So much for learning from history. Of course, the Biden administration claimed that in withdrawing it was merely taking a hardheaded approach, finally drawing down an indisputably overlong commitment to the country. But the manner of the withdrawal and the weakness it projected have had profound implications.

Many experts believe that Vladimir Putin’s long-held desire to annex Ukraine was sparked into action by the ineffectual way in which the US withdrew. Worse is that the axis on which the global order moves has subtly shifted in the resulting period. For instance, if you are going to make one big mistake in a region, you had better make sure that every other alliance is in very good working order. The necessary isolation of Russia since its aggression in Ukraine has certainly pushed Russia closer into its own axis, of China and Iran. A motley collection of countries, to be sure, but far from being without clout, and all the more reason to shore up your natural allies.

The Biden administration has been exceptionally poor at doing that. Israel is generally thought of by outsiders as being almost de facto within the orbit of America. But the fraying of that relationship during the Obama administration (during which Biden was vice president) is undeniable. During that time, Israel inevitably had to keep other lines of friendship open, including with Russia. So Israel has, as a matter of realpolitik, kept itself out of the clear demarcations the rest of America’s allies have held to since the start of the Ukraine crisis. Such things happen once you take to hectoring allies, rather than working with them. Until recently, there were few similarities between the Israelis and the Saudis. But Biden has managed to create some.

He publicly berated the crown prince for the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, and, as a result, the Saudis have been ever less inclined to simply do the bidding of Washington. With energy prices soaring last summer due to the fallout of the Ukraine war, Biden personally went to Saudi Arabia and asked them to increase oil production. There was a time when an American leader just needed to pick up the phone. But with midterms looming, Riyadh actually cut production. It was an amazing middle finger, a sign not only that the Saudis didn’t need to do what the US asked, but could do the opposite if they chose.

In such a situation, dangerous new alliances form. What has been most striking in the past year has been the audacious efforts by the Chinese to step into the roles once expected of the US. If there was a peace deal to be brokered in the Middle East, it used to be assumed that it would be America that would broker it. No more. When a deal was agreed in March to restore relations between the bitter enemies Iran and Saudi Arabia, it was Beijing that brokered it. Around the same time, it was the Chinese leadership that started touting a “peace deal” to end the war in Ukraine. That “deal” was the minimalist Russian position that Moscow should be allowed to retain territory that it has annexed. But as the Ukrainian counteroffensive makes slow progress, many nonaligned countries see China at least providing some solution to the conflict. The Americans, meanwhile, just talk the language of taking “as long as it takes”. And whatever your views on the Ukraine conflict, it is hard to deny that the line from Washington has changed again and again.

Munitions that are ruled out one month are passed another month. Tanks and planes are presented as unthinkable to provide one month and provided the next. None of this is helped by the sheer lack of confidence that anybody dealing with the US president himself must feel. Last month, Biden held a meeting at the White House with the Israeli president Isaac Herzog. The hope was that it would reassure Israelis that the relationship was as solid as ever. This came at the same time as Biden was chiding prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu for his judicial reforms. That in itself is a classic Biden misstep. What business is it of the Americans if the Israeli government chooses to make long overdue changes to its supreme court system? Would anybody expect Netanyahu to step in and criticise the US government when the US supreme court is politicised? The idea is preposterous, but the belief that the Americans have the right to lecture everyone in the region is built into the system, when what America’s allies need is encouragement beyond words or occasional photo ops.

Tehran is once again extorting the US by demanding money for prisoners. Iran has been a rogue state since 1979, but there are few rogue states in the world that America is so constantly and successfully blackmailed by. Expect pallets of cash to be handed over once more, as during the Obama-Biden years, to a regime dancing on the edge of trying to become a nuclear power.

For many countries in the region, Saudi Arabia and Israel perhaps most of all, that is the nightmare scenario, an Iran that goes nuclear fast. But then, Iran is in a good position. It has some strong friends – principally China – and some weak enemies, including the US. As I say, a subtle shift in the axis of global power. But on such subtle shifts whole worlds can change.