Simon Urwin

Located in the heart of Central Asia, Karakalpakstan is the “stan within a stan”, an autonomous state of the landlocked Republic of Uzbekistan that borders Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. Home to the Indigenous Karakalpak people, the desert province was, until recently, dominated by the Aral Sea – a vast inland lake that has since shrunk to a fraction of its original size.

Considered one of the most serious environmental disasters of modern times, the Aral Sea’s fast-disappearing waters have spurred on conservation efforts here, leading to a growing interest in Karakalpakstan as a destination for eco-tourism.

Those visitors have, in turn, started to seek out the region’s cultural treasures, too. “The Khorezm desert fortresses and the Mizdarkhan necropolis here are amongst the most-impressive archaeological sites anywhere in Central Asia,” said Sophie Ibbotson, co-author of the Bradt Guide to Karakalpakstan, the first-ever travel guide to the region. “Elsewhere, the Savitsky Museum in the capital Nukus is justifiably known as the ‘Louvre of the Steppe’.” (The museum contains the world’s second-largest collection of Russian avant-garde art alongside Karakalpak archaeological and ethnographic galleries.) “For the intrepid traveller, this is a land of extraordinary variety, both in terms of landscapes and experiences.”

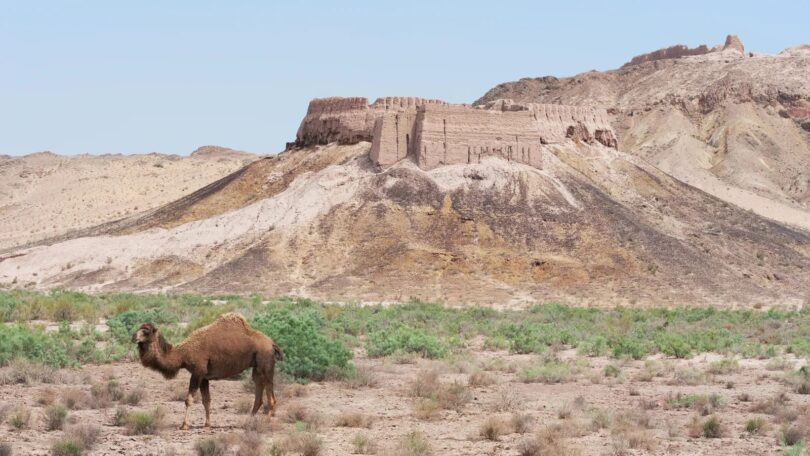

Karakalpakstan was once part of a historic region known as Khorezm, whose people built great mud-brick fortresses along their frontiers as protection from nomadic raiders. More than 50 of their desert castles have survived, including Ayaz Kala, which dates to the 4th Century BCE and consists of two hilltop forts and a lower garrison. One notable discovery here was the remains of an ancient fire temple, believed to have been the altar of fire-worshipping Zoroastrians. (Zoroastrianism was practiced in Karakalpakstan before Islam arrived in the 8th Century.)

Until the early 20th Century, many Karakalpak families lived in yurts: portable tents that were ideal for the seasonal migration with their cattle between winter homes and summer grazing pastures. They consist of a lightweight wooden frame covered with animal skins and wool, the latter said to deter desert scorpions.

In the city of Chimbay, Azamat Turekeev is a third-generation yurt maker who builds around 18 yurts a year, the largest of which cost $3,500 (£2,800). Turekeev sells to some Kazakh and Kyrgyz nomads but mostly now to tourist yurt camps. “The rise in adventure tourism helps keep this ancient tradition alive,” he said.

Founded in the 4th Century BCE, Mizdakhan is one of Karakalpakstan’s oldest and holiest sites. According to local legend it’s the burial place of Adam. (In the Islamic creation myth, Adam was the first human, the first prophet of Islam and the first Muslim.) The necropolis was part of a larger city inhabited for 1,700 years until it was destroyed by Timur, the great conqueror of Central Asia. After its demise, the site continued to attract pilgrims who built mausoleums and small mosques, some of which have survived largely intact since the 11th Century.

Kenyes Ilyasov has been the imam at Mizdakhan for more than 20 years and often receives the faithful in the crypt of Shamun Nabi, an early follower of the Prophet Mohammed whose 33m-long sarcophagus is said to grow by an extra inch each year.

All Muslim visitors to Mizdakhan’s necropolis are expected to pass by a crumbling mausoleum that loses a brick every year and is known as “the apocalypse clock”. “When the last brick falls it will signify the end of the world,” said Ilyasov. “So all good Muslims should return a brick to the structure just in case.”

Sulukhan Kuptileuva sells smoked fish in Nukus’ main bazaar. She has been smoking fish for almost 25 years, a skill passed down from her grandparents. Her speciality is smoked carp, which is traditionally served fried with a glass of beer or a shot of vodka.

“I salt the fish for a week and smoke with fir, which gives a deep, woodsy flavour,” she said. “Back in the 1950s and ’60s the fish would come from the Aral Sea. Now they are all gone, everyone has to raise catfish and carp in their own private lakes.”

One of the most iconic pieces on permanent display at the Savitsky Museum is a sculpture by renowned local artist J Kuttimuratov, which depicts Karakalpakstan’s so-called mother river, the Amu Darya, a tributary of the Aral Sea, which was known to the ancient Greeks as the Oxus.

“It’s the first in a series of three artworks,” said museum guide Sarbinaz Majitova. “Each one decreases in size; they represent the fast-disappearing waters and the diminishing power of this great symbol of life and fertility.”

The Aral Sea was once the fourth-largest lake in the world, covering 68,000 sq km – an area equivalent to the size of Sri Lanka. Over a period of 50 years, it has shrunk to just 10% of its original size. The sea’s decline began in the 1960s when the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers were diverted to irrigate cotton crops. Deprived of its tributaries, the Aral Sea began to disappear, resulting in widespread loss of flora and fauna, the decimation of local fishing communities and the creation of the world’s newest desert: the Aralkum.

Once a wealthy fishing port, Moynaq is now a harbour without a sea, its fishing fleet left adrift in the desert. Despite extensive damage to the local ecosystem, Ibbotson believes there remains cause for hope. “The Aral Sea is a reminder of the resilience of nature,” she said. “There is still some lake water, which attracts native and migratory bird species including flamingos. The critically endangered saiga antelope population is recovering, and local animal and plant life are adapting to the new conditions. It is inspiring.”

In the village of Kubla Ustyurt, Dusenbay Usenov and his wife Zarifa Khudaybergenova once made a living in the local fisheries, but now survive from selling fermented camel milk (shubat) to locals and tourists. Tangy and mildly fizzy, shubat is a popular beverage throughout Central Asia, said to aid digestion.

“The shrinking Aral Sea has impacted directly on the lives of those who live closest to it,” said Khudaybergenova. “But it is also a warning to the rest of the world, of what might happen if we don’t all take better care of it.”

Courtesy: BBC