Giovanna Dunmall

Despite its seemingly anodyne title, The Laboratory of the Future, this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, curated by Ghanaian-Scottish academic and novelist Lesley Lokko, is anything but.

Shifting from a more formal, classically trained Eurocentric notion of architecture to something fresher, more improvised and nimble, the biennale, which runs until November 26, appears more connected to locale and context than before. The laboratory part of the title suggests experimentation and radical rethinking.

Though the national pavilions are not directly curated by Lokko, or even tasked to stick to the main themes of looking to the future, decolonisation and decarbonisation, many have chosen to use these ideas as guiding references.

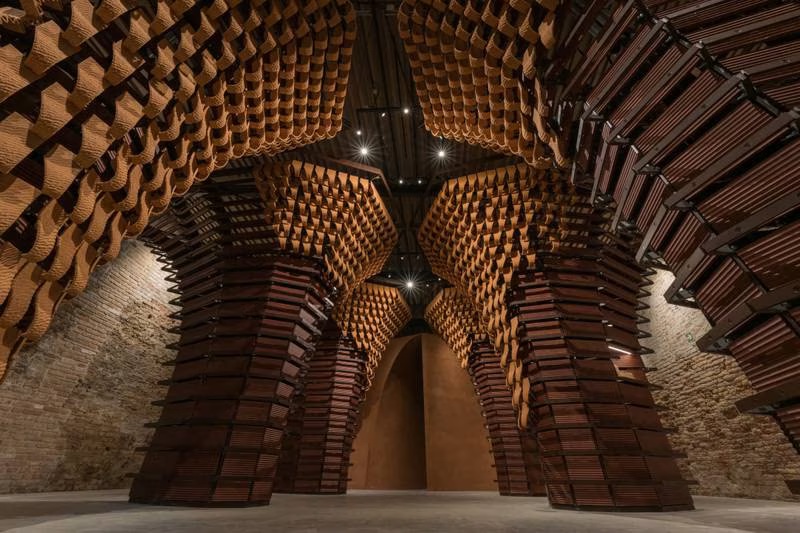

The National Pavilion of Saudi Arabia is no exception, eschewing shiny or monumental gestures for a series of more traditional yet still alluring spaces with arches on either side of a rectangular central room that feels almost cave-like and prehistoric.

Inside the dimly lit central space is just one object – a hollow 3D-printed clay column with a mashrabiya pattern from which light is projected on to the floor, walls and ceiling. This object, and others that will be made throughout the biennale, will be relocated to the bottom of the Red Sea once it is over, where they will create new habitats for marine life and leave a legacy – as the pavilion’s Arabic title Irth, which means legacy or heritage, hints at – for future generations.

In much the same way, the faceted columns of the pavilion’s arches evoke ancient gateways but are actually made of rows of 3D-printed clay tiles adorned with patterns inspired by undulating desert dunes and the vernacular architecture of Asir, a region in the south-west of the country that consists of coastal plains and high mountains.

Similarly to the illuminated object in the central space, these tiles meld together artifice and nature, technology and history.

It is in this long cavernous central space that one can also smell a fragrance created specifically for the pavilion.

“It was designed to capture elements of the culture,” explains assistant curator Joharah Lou Pabalate. “We have frankincense, which was a core element of our trade routes, we have myrrh and we also have lavender, which is, perhaps surprisingly for some, part of our flora. It’s our way of introducing Saudi Arabia to the world.”

Pabalate goes on to talk about memories linked to scent and says that growing up in the kingdom she was welcomed into the homes of friends by the smell of bahur, or incense, and that this smell always brings to mind “reminiscences of what the home is”.

What the architects and curators are honing in on here is the intangible (a word that comes up repeatedly) aspect of architectural space and cultural heritage.

“It’s truly the missing factor,” says Pabalate. “When we talk about architecture we always forget the unseen and focus on the visual, but memory and meaning making is really about what we don’t see because it’s something that’s ingrained in you.”

There is something very true about these words and soon everyone in the central part of the pavilion is exchanging early or first memories linked to smell. These range from the scent of Jasmine to far more prosaic mothballs or the plastic smell of a freshly unwrapped G I Joe toy.

It’s a nice moment of collective sharing spawned by, of all things, a scent at a Biennale. And brings me on to pavilion architect AlBara Saimaldahar’s words at the opening.

Calling the space “an homage to the essence of Saudi vernacular architecture and its evolving landscape,” he says that “by utilising innovative technologies, and adapting traditional forms, patterns and materials, we wanted to provoke a contemplation on the role of the collective in the legacy of the built world.”

The collective is a big theme in this pavilion and more widely in this year’s Biennale. The curators of the Saudi pavilion, Basma and Noura Bouzo, are also keen to emphasise this when they say the pavilion is “a collaborative effort … that seeks to finds common ground in its desire to improve the human condition and answer the challenges confronting our world.”

In practice, what this means is that aside from being a series of beautiful, tactile and scented spaces, the pavilion also functions as a sort of incubator where you can find out more about the latest material experimentations in Saudi Arabia displayed in open vitrines dotted around the arches.

On display is some incredibly lifelike 3D printed coral created by the Coral Research & Development Accelerator, which is located at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology.

Coral reefs are created by tiny marine animals that secrete a calcareous skeleton and are some of the most complex and vital three-dimensional structures on earth, providing vital coastal protection and homes to marine life.

As coral reefs grow very slowly and they are increasingly under stress from ocean acidification, these 3D printed models are being used to restore and replenish coastal marine landscapes in the Red Sea.

There is an interesting link here to vernacular and historic construction materials and techniques used in Jeddah’s historic district of Al Balad. Fossilised coral limestone blocks up to 250,000 years old were used in Al Balad for their porous properties and abilities to insulate against the salty air. The blocks were bound with a mortar made of lime and clay from the seabed.

Elsewhere, we see compressed building blocks made of soil and crushed stone – a sort of local rammed earth – and woven palm panels conceived by Riyadh-based Syn Architects that can be used to make roofs or shading structures, as well as walls and screens.

Both are made of elements found in abundance in Saudi Arabia, the latter in particular as the country has more than 31 million palm trees.

Samantha Cotter and Roth Architecture experiment with salt brine by combining various forms of salt with calcium carbonate, borax and recycled polypropylene respectively.

As a by-product of the desalination processes, salt is also plentiful in the region and not typically used in construction. Potential future applications that are being developed include wall finishes, tiles, screens and lamps.

When viewed as a whole, the pavilion can be seen as a bridge between the past and the future, as well as a workshop for the creation of new materials. It presents a case for a technology-led Saudi vernacular architecture that has yet to fully materialise, but is clearly well under way.

Courtesy: thenationalnews