Aysha Imtiaz

Paratha rolls – tender, juicy kebab or bite-sized chunks of grilled meat smothered with tangy chutney, garnished with onions and rolled in flaky, crispy fried flatbread (paratha) – are to Pakistanis what hot dogs are to Americans; they are at the culinary core of the frenetically paced city of Karachi. In this ethnically and linguistically diverse metropolis, paratha rolls are one of the few creations the city can proudly claim as its own. It’s not so much a question of whether you’ve tried them, but which one is your favourite.

The central premise is simple – just wrap a kebab in a paratha. But Masuma Yousufzai, a Karachi local who grew up eating paratha rolls, says it’s the marriage of the two staples that stands out. Typically, kebab and paratha are eaten by tearing off pieces of the bread to scoop up the meat, but putting the bread and meat in one roll makes it greater than the sum of its parts. For Karachi residents, the food has always captured the zeitgeist of the times in one daring, delicious parcel.

“[Holding] it all in your hands and being able to eat it all at the same time – with the chutney dripping out – lets you taste that melody of flavour in every bite. Somehow, it makes the whole experience a lot better. And tastier,” Yousufzai said.

The backstory is as satisfying as the food. In 1970, Hafiz Habib ur Rehman created the now iconic kebab rolls quite serendipitously during a particularly busy day at his local snack bar called Silver Spoon Snacks in Karachi’s famed shopping street, Tariq Road. Newly established at the time, Silver Spoon initially served a plate of kebab and paratha, as well as chaat (a savoury chickpea snack) and ice cream. On a whim one day, when a customer was pressed for time and couldn’t sit down to enjoy his food, Rehman hastily rolled the kebab into a paratha for him, wrapped it in wax paper and handed it over. Another customer standing close by requested the same. Rehman soon realised this wasn’t just efficient – suddenly, he had fewer dishes to wash, seating space was freed up and customers were served swiftly. It was also novel and exciting.

“When we first introduced the kebab roll, waiters had to explain to customers that it wasn’t meant to be unwrapped and eaten like roti,” he said. Initially, Rehman gave away the rolls for free, tucking them into orders of more familiar items such as chaat or walking up to cars at the nearby Liberty Chowk (roundabout) traffic light like a newspaper hawker in the hopes that paratha rolls would catch on.

They did.

At the time, newer fast-food businesses in Karachi were focused on Western-style burgers and sandwiches and frowned upon Rehman’s curious “kebab in paratha rolls”. They relegated the rolls to the land of bun kebabs and humble street food, but the creation became a revelation nonetheless.

In little more than half a century, paratha rolls have become a ubiquitous and unrivalled part of the repertoire of South Asian street food, enjoyed across the borders in India and Bangladesh as well as Pakistan, though their birth city of Karachi is where they are most popular.

According to Dr Sahar Nadeem Hamid, professor at the Institute of Business Administration in Karachi, having a paratha roll was a way for Pakistanis to experience the novelty of eating “fusion food” – traditional food served in a contemporary way – without venturing too far out of their comfort zone. “In the ’70s, we didn’t have too many eating out options that were not too expensive,” she explained. “The Irani cafes were where most people ate out, but they tended to be more expensive than [places where] the paratha roll [was served]. The food carts were cheaper but less of a dining out experience. Silver Spoon took local flavours and presented them as fast food, which was also economical.”

The food matched the fast-paced lifestyle of the migrant-heavy and upwardly mobile population. “You could eat a roll if you felt hungry in the middle of a shopping trip, or the office workers in the nearby offices could have a quick meal for lunch. It could also be a family outing… for a change from home-cooked food,” said Hamid.

Paratha is fried until flaky and crisp (Credit: Aysha Imtiaz)

Throughout the 1970s, paratha rolls skyrocketed in popularity among youngsters for their affordability and convenience, and with elders for the familiar taste. They were easy enough to be consumed in public transportation or while walking or driving, clean enough that the slick oiliness stayed on the wax paper and the hands remained clean – and desi, or local, enough to suit established tastes.

For women especially, having the option to grab the roll and eat on the go – instead of sitting in a restaurant or cafe alone to dine – helped from a sociological perspective. At Silver Spoon, this was an especially important factor as the restaurant’s limited seating meant customers were often very close to the male servers and chefs, explained Rehman.

Silver Spoon soon spawned an entire industry. Many popular paratha roll joints opened and created veritable empires, such as RedApple, Hot-N-Spicy and Mirchili. But for those who experienced paratha rolls when they were just gaining popularity in the 1970s, the experience of Rehman’s tawa paratha (a paratha shallow fried on a large flat griddle called a tawa) with its tangy brown chutney and tender beef, is steeped in nostalgia. Rehman said that when Pakistanis living abroad come back, many drive to Silver Spoon straight from the airport to get their fix, even if it’s been 20 to 30 years since they’ve returned. It’s a homecoming.

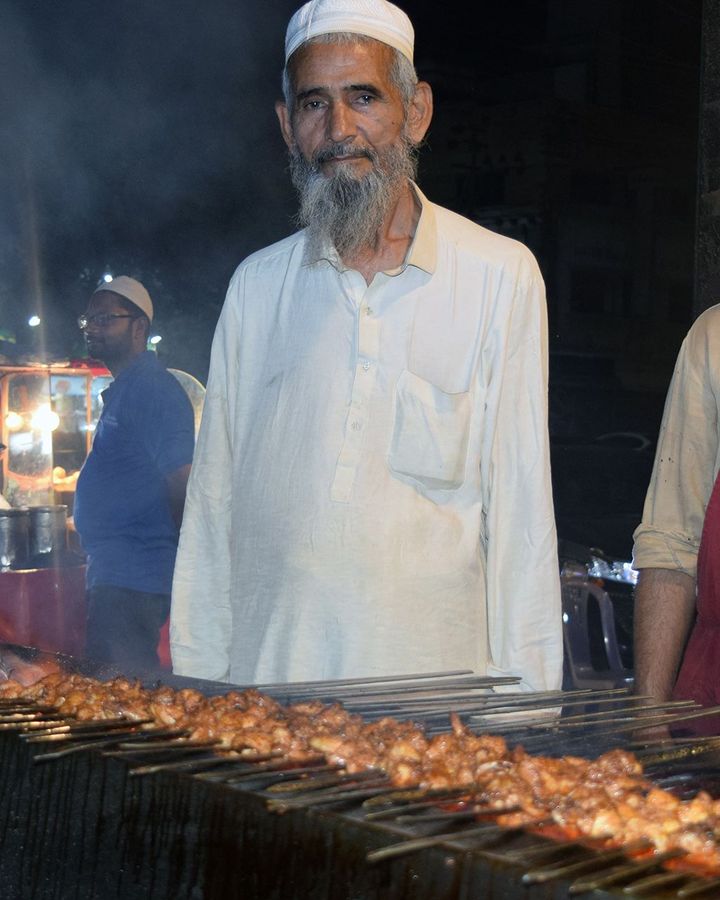

A Karachi vendor makes the kebabs for paratha rolls (Credit: Aysha Imtiaz)

In 2019, in an attempt to cash in on paratha rolls’ phenomenal success, KFC introduced the Zingeratha, a combination of KFC’s Zinger Burger (starring spicy, breaded, crispy fried chicken) and paratha. Early television commercials carefully positioned it as the solution for younger consumers who weren’t sure if they wanted to eat “desi” or “Western” food. “It’s not confusion. It’s fusion,” KFC proclaimed. But when Pakistanis tried it, the response was underwhelming. Paratha rolls were meant to be a fusion of the way two beloved Pakistani foods were eaten – not a hybrid between local and foreign tastes.

“KFC tried to jump onto the bandwagon by launching their Zingeratha [but] it did not work in capturing the essence of our favourite paratha rolls. [It was] a soggy, thick paratha [with] too much mayonnaise and a sweet sauce instead of spicy chutney. We feel KFC should stick to their classic bucket of fried chicken,” said Zulekha Ahmed, founder of food blog @karachifoodadventure. “The authenticity of [our] rolls comes from the chutney prepared on the street, onions cut roughly by the street vendor, marinated chicken boti [small chunks of grilled meat) barbecued live on the charcoal with its smoky smell and melt in the mouth experience. The cleaner, fusion version in the form of Zingeratha was too far from that authentic feel.”

Zia Tabarak, who runs the YouTube channel Street Food PK, agreed. “[It’s not just] Zingeratha’s name that’s foreign,” he said. “It also lacks that Pakistani flavour and feeling of belongingness that the paratha roll has.” Though the Zingeratha is still on KFC’s menu and has its customers, it’s a wildly different experience that can’t capture the je ne sais quoi of the street paratha roll.

Putting a positive spin on things, he added, “I think that this is an achievement for the paratha roll, that a food chain like KFC imitated it. But the original will remain as it is, and it can never be fully imitated.”

Courtesy: BBC