Nicole Melancon

It was midmorning as my guide, Singay Dradul, and I approached a verdant valley in the district of Wangdue Phodrang. We had come from Pele La, one of Bhutan’s highest passes at 3,407m, which marks the boundary between the west and central parts of the Buddhist Kingdom. Over the past two hours of hiking, we had barely seen a soul except for a group of semi-nomadic yak herders who had recently come down to lower elevations for the winter.

We walked past a farmer, who greeted us warmly. “Kuzuzangpo la (hello). Have you seen my calf?” he asked in Dzongkha, the national language. It had gone missing earlier in the day and he feared it had been attacked by a pack of wild foxes. Or even worse, a tiger.

A female Bengal tiger had been roaming the area for the past few months attacking livestock and putting the farmers on high alert. While she had not been spotted in the exact area we were hiking, I still felt uneasy. Was she lurking somewhere behind the thick forest cover, waiting to pounce?

Luckily the village of Rukubji, where we would stop to enjoy a hot farmhouse lunch, was only half an hour away. We continued on through the wide-open fields, thankfully moving away from the forest. It was my second day hiking the newly reopened, 500-year-old Trans Bhutan Trail (TBT) with Dradul, and I knew I was in good hands.

The TBT dates back to the 16th Century when it was the sole means of transportation for rulers, pilgrims, monks, traders and legendary trail runners known as “garps”, who delivered political messages to the dzongs (fortresses) throughout the country. At its height, the TBT had significant socio-economic, political and spiritual meaning, bonding communities into a nation. Stretching 403km between the towns of Haa in the far west and Trashigang in the east, the TBT crosses 27 gewogs (villages) and nine dzongkhags (districts) of Bhutan.

Host Dechen Zangmo and guide Singay Dradul hike near a Bumthang farmhouse (Credit: Nicole Melancon)

After the construction of Bhutan’s first national highway in 1962, the trail was no longer used as the main route of transportation. Bridges, footpaths and stairways collapsed over time as the maintenance of the trail was neglected. The revival of the ancient trail after 60 years of misuse was a vision by His Majesty the King to preserve Bhutan’s unique past from the threat of growing modernisation that has left the old trail and its history almost forgotten.

“It is like a living, walking museum,” Dradul said, referring to the TBT. “It is filled with stories, myths and legends. I’m worried that it will soon disappear if we don’t protect it.” The hope is that the TBT will be used by locals, tourists and future generations to hike, mountain bike, trail run and, most importantly, connect with rural Bhutanese culture and history.

Dradul was one of the first of two guides to hike the entire TBT before it opened in September 2022, working as a trail inspector for the non-profit social enterprise the Trans Bhutan Trail organisation. Along the way, Dradul began establishing a network of farmhouses that offer tourists a rare glimpse into rural life in Bhutan by welcoming guests into their homes to eat and stay. Together with the Trans Bhutan Trail organisation, Dradul and other guides are setting up a Trans Bhutan Trail Passport programme where tourists can get their trail passport stamped when stopping at participating farmhouses along the way. To date, there are more than 60 “Passport Ambassadors” who host visitors; they’re spread across the kingdom and most of them are women.

Through the Passport Ambassador programme, local farmers open their homes to serve tourists a traditional meal while sharing their culture and heritage with their guests. Some offer cooking demonstrations, while others indulge guests in traditional hot stone baths. For a more immersive experience, travellers can even spend the night. This grassroots partnership not only empowers women to work in tourism and earn a sustainable income but also provides guests with a deep cultural understanding and connection with some of the most remote communities and people in Bhutan.

A hot farmhouse lunch in the village of Rukubji (Credit: Nicole Melancon)

As we entered the traditional mud-rammed farmhouse in Rukubji, we were greeted by Rinchen Dema, the owner, who shares the house with eight members of her extended family. Per tradition, as the oldest daughter, she has been in charge of the household since her mother passed away.

“It is good that you are here,” said Dema, while pouring us a hot cup of hot suja, a traditional butter tea dating to the 7th Century. “Just yesterday, the tiger killed another cow in the neighbouring field. It is best you end your hike here for the day.”

I sipped my suja slowly, letting the surprisingly satisfying taste of yak butter, salt and tea warm my soul and quell any lingering fears of the tiger. A few minutes later, Dema and her sisters carried over plates piled with food and a huge bowl of red rice setting them next to us on the floor. “This is jaju (a traditional Bhutanese soup made of spinach and milk), chicken curry and buckwheat pancakes, all grown from our farm organically,” Dema said.

As we sat on large colourful floor cushions, Dema handed me a fork. Dradul and the others grabbed a small piece of rice, rubbed it between their fingers to clean their hands, and began to eat. I soon realised that in Bhutan, no one except tourists eats with silverware. I placed a bite of chicken curry in my mouth and was astonished by its delightful, spicy flavour. The meal was hearty and rich, satiating my hunger from our morning hike.

After a tour of the Rukubji’s community farm, our driver Dorjee drove us to our next stop, the town of Trongsa where we would be spending the night. We wouldn’t be continuing our hike to the next village of Chendebji that day, nor would Dema be seeing her married sister who lives a 30-minute walk in that direction any time soon. “As a farmer, it’s a risk to live with tigers, especially now that there is a mother with cubs nearby. But it is the life we live in Bhutan. One with nature,” explained Dradul.

Dechen Zangmo welcomes guests and teaches cooking classes in her farmhouse (Credit: Nicole Melancon)

Two days later, Dradul and I were further east in Bumthang, one of Bhutan’s most sought-after destinations with its pastoral landscape, rich local culture and sacred historical pilgrimage sites. After hiking the TBT through rhododendron and pine forests down into a fertile valley of buckwheat and potato fields, we came to the tiny, remote village of Tang Bebzur containing only a handful of homes. There, we were welcomed into a farmhouse by Dechen Zangmo, a wife and mother of two daughters. Dressed in a purple-and-white striped kira (traditional Bhutanese dress) with a blue flannel shirt for extra warmth, Zangmo’s unwrinkled face and bright smile made her look much younger than her age.

After removing my shoes and receiving a welcome drink of butter tea, Zangmo excitedly whisked me away into her small kitchen where she demonstrated how to prepare Bhutan’s staple dish, ema datshi (chilli with cheese).

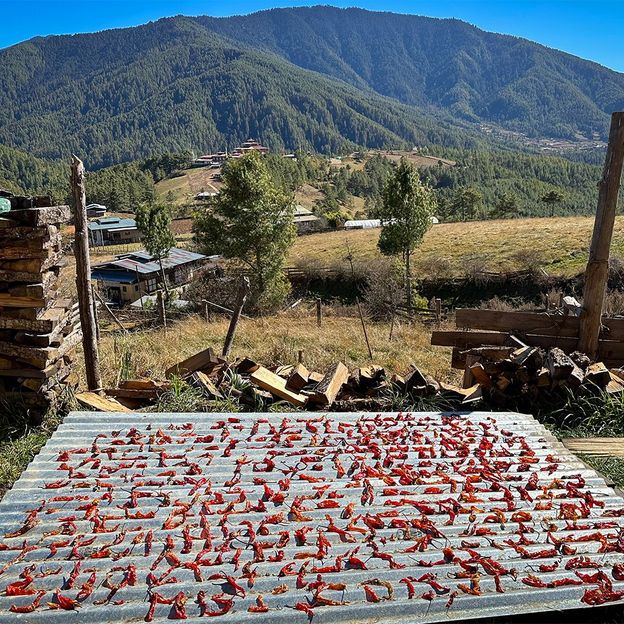

“In Bhutan, chillies aren’t used a spice, but as a vegetable, as the main ingredient,” explained Zangmo as she showed me how to break the dried red chillies apart and mix them in a saucepan loaded with butter and cheese. As I stood beside her, my eyes watered, and I marvelled at how hot and spicy Bhutanese cuisine is. Chillies are so well loved that Bhutanese dry them anywhere they can – on rooftops, hanging from the window and across the ground.

Bhutanese dry chillies on rooftops, hanging from windows and across the ground (Credit: Nicole Melancon)

Along with ema datshi, Zangmo offered me the region’s famous margu, a homemade chapati bread made with local buckwheat, and followed the meal with a drink of home-brewed ara, the local wine made throughout rural Bhutan.

“I wanted to open the doors of my farmhouse to tourism in 2018 but then the pandemic hit and ruined my plans,” said Zangmo. “Then last year, a guide from the TBT knocked on my door and invited me to be an ambassador, which changed my life. Not only can I make some extra money for my family, but I also have the opportunity to interact with people from around the world and learn new things.”

As we sat cross-legged on the floor, talking and sharing the meal we had just created together, I couldn’t think of a more intimate way of experiencing Bhutan. I realised how lucky I was to see the local treasures that hardly any tourists ever get to experience.

On my last night in Bhutan, Dradul took me to the house of a close friend, Thinley Yangzom, who runs the Tshering Farmhouse in Paro. Yangzom’s farmhouse has been in the family for six generations, and she is a TBT ambassador and an entrepreneur in organic farming. That night, I was to be a special guest of their zaa-tschang, the Bhutanese word for “family”.

As I stood in the kitchen watching Yangzom prepare our feast of pumpkin soup, homegrown quinoa, pork and radish stew and, of course, chilli and cheese, I was at ease.

Thinley Yangzom runs the Tshering Farmhouse in Paro (Credit: Nicole Melancon)

I had just taken a traditional hot stone bath and had completed an extraordinary five days of hiking as the last guest of the season on the Trans Bhutan Trail. And now, chatting with Yangzom and playing with her two young kids, I felt like I was part of their zaa-tschang.

Courtesy: bbc