Malavika Bhattacharya

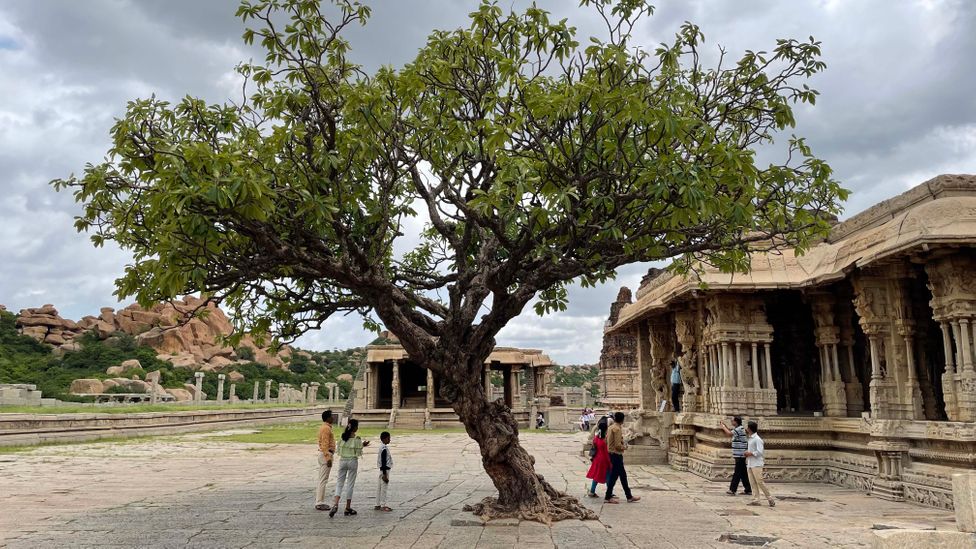

Squinting under the bright South Indian sun, I could see piles of boulders strewn haphazardly in the distance, while around me were intricately designed gateways, pillared pavilions and huge sculptures. I was in the city of Hampi, which is known for two main things: its unusual terrain of granite rocks in varying tones of grey, ochre and pink; and the ruins of centuries-old temples and palaces. Where I was, in the compound of the 15th-Century Vijaya Vithala Temple, the two collided.

A Unesco World Heritage site, Hampi is often described as an open-air museum, filled with magnificent stone ruins on the banks of the River Tungabhadra. As the capital of the South Indian Hindu Vijayanagara kingdom from the 14th to 16th Centuries, the city was ruled by kings who lavishly spent on culture, religion and the arts. The Vijaya Vithala temple, which is dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu, is an architectural masterpiece whose soaring columns and massive gateways are all hewn from the porphyritic granite found in the region.

Around 500 years ago, Vijayanagara royalty and citizens would come to this temple to pray, celebrate and be entertained. As I looked around, I could see elaborate pavilions featuring iconography of Hindu mythology carved into the stone. The grandest among them was the Mahamandapa (Great Hall). Grand balustrades flanked by stone elephants led up to the pillared hall, which sat atop a stone platform carved with motifs of horses and flowers. Filled with soaring stone columns and intricately carved sculptures, this pavilion served as a stage for classical dancers to perform for the king and for the gods.

The Mahamandapa is the grandest of the pavilions at the Vijaya Vithala temple (Credit: Images of India/Alamy)

“Imagine,” said my guide, Manjunath, “The sounds of the veena, the tabla, the jaltarang [classical Indian string and percussion musical instruments] filling this space.” I visualised dancers whirling around the pavilion as musicians played beautiful melodies on their wind instruments, strings and percussion amid Hampi’s barren, rock-strewn backdrop.

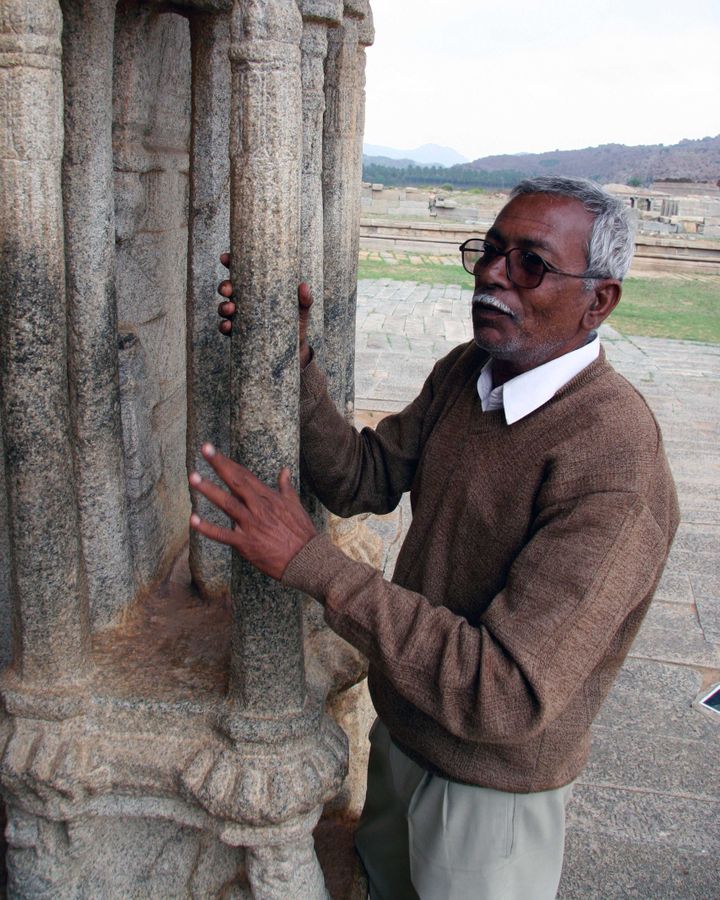

But then Manjunath pointed to the stone pillars that rose around us. “These were the only musical instruments used here,” he added, rather mysteriously.

Hampi’s “musical pillars” are a phenomenon that has baffled people for centuries. Hewn from single blocks of granite, the 56 pillars within the Mahamandapa pavilion are often referred to as the “singing stones” or the “sa-re-ga-ma pillars” (sa-re-ga-ma is the Indian classical music scale, like do-re-mi-fain Western music).

In the olden days, musicians used to ‘play’ these slender columns with sandalwood sticks or their fingers, producing the sounds of different instruments

“In the olden days,” said Manjunath, “musicians used to ‘play’ these slender columns with sandalwood sticks or their fingers, producing the sounds of different instruments.” He explained that when struck, the pillars produce different musical notes as well as the sounds of various Indian instruments like the ghanta (bell), plus percussion instruments like the damaru (a small handheld drum)and mrindangam (an oblong double-sided drum).

Hampi’s “musical pillars” are a phenomenon that has baffled people for centuries (Credit: Malavika Bhattacharya)

Musical pillars are unique to a handful of South Indian temples, and the craft was most notable during the Vijayanagar era. They vary in style, and Hampi’s pillars are remarkable for their intricate workmanship on hard granite. “Although we have examples of lithophones [resonant stones] in other parts of the world, there’s nothing quite like Hampi’s pillars in terms of art historical and aesthetic significance,” said Sharada Srinivasan, professor of archaeological sciences at the National Institute of Advanced Studies Bengaluru.

Curious about these “singing stones”, I peered up at the Mahamandapa for a closer look at the pillars extending deep into the interior. The pavilion is cordoned off to visitors in an attempt to preserve these stone relics, since people repeatedly banged on the stone shafts to produce musical notes, leading to their degradation. Now, tourists can only see and not touch these centuries-old columns. In fact, many pass by them without realising their immense value.

I gazed in awe at the smooth shafts, marvelling at their rich carved bases and tops. These are composite pillars, meaning that each individual pillar is made up of multiple parts: a thick load-bearing central column surrounded by a cluster of slim stone colonettes. I saw sets of two and four columns, as well as tightly packed groups of 10 and 14. The slender pillars varied in shape and design: some were circular, while others were hexagonal, square and octagonal. Some were adorned with sculptures of musicians and dancers.

Musicians would ‘play’ the columns using sandalwood sticks or their fingers (Credit: Barry Vincent/Alamy)

As my guide painted a vivid picture of music and dance in this magnificent space, questions swirled through my mind. Do these stones actually sing? And if they do, how do they work?

My first thought was that the pillars were likely to be hollow inside, thus producing amplified reverberations when struck. Manjunath quickly dismissed my theory. In the past, he said, some pillars were sliced into to try to decipher the mystery, revealing only solid rock.

It does bring to mind the seven musical notes in ascending and descending order – the sa-re-ga-ma scale

According to Srinivasan, “The pink porphyritic granite found in this region has resonant qualities in some places, especially in thinner sections.”

She explained that while not all the 56 pillars in the Mahamandapa emit musical notes, some of them, like the 14-pillared cluster, definitely do produce tonalities when struck. “It does bring to mind the seven musical notes in ascending and descending order – the sa-re-ga-ma scale,” she said.

Heritage architect Meera Natampally, who is an expert in South Indian temple architecture, agrees that the musical sounds are due to the qualities of the rock. “There is no chemical imparted to the stone to produce these notes,” she said.

Hampi is known for its elaborate architecture such as stepwells (pictured) and palaces (Credit: Malavika Bhattacharya)

While working on the visual reconstruction of the Vithala Temple complex, Natampally and metallurgists at the site concluded that the original location of the stone plays a role in the sound of the pillars. “The granite used [for the pillars] comes from different local quarries, so you have different stones that produce different sounds.” She also believes that the pillars’ shape, size and positioning play a part in determining the sounds they produce.

I’d thought that all the slender pillars seemed uniform, but on closer examination I saw that they varied distinctly in their girth, in their distance from the core pillar and even their length. “Where the column is placed is very important,” said Natampally. “For instance, if there are four colonettes in a cluster, the ones at the back produce a different sound.”

Srinivasan explained that the sculptures around the pillars also relate to the sounds they produce. Citing the example of a pillar featuring a now-damaged sculpture of a musician in a classical Indian Bharatnatyam dance posture, holding cymbals in his hands, she said, “There are two rhombus-shaped colonettes there that give off a higher pitch, suggesting a correlation with the cymbals.”

While historical texts give us accounts of festivities and performance at the temple, there are no records detailing how the pillars were constructed. In 1565, the Vijayanagara empire fell in the Battle of Talikota against the Deccan Sultans – a coalition of Islamic dynasties in the South Indian Deccan peninsula. When Hampi was sacked, many grand monuments were destroyed and Vijayanagar lay in ruins. Both physical structures and knowledge of the time were lost. So the question remains: were these pillars intentionally built to be musical, or are the notes they produce simply a byproduct of their design?

Although musical pillars can be found in other South Indian temples, Hampi’s pillars are remarkable for their intricate workmanship on hard granite (Credit: Malavika Bhattacharya)

Looking up at some of the more worn and weathered columns, I considered various possibilities: maybe people accidently discovered that the pillars produced sounds and began using them as musical instruments; or perhaps the artisans of Vijayanagara chiselled away at the stone until it gave them the sounds they wanted.

However, the truth is that we’ll likely never know for sure.

“As far as the acoustics are concerned, there’s still a lot to be unpacked. It’s uncanny that so much could have just been achieved by chance,” said Srinivasan.

In the spiritual city of Hampi,where myths and legends fly thick and fast, it’s easy – and tempting – to imagine a medieval orchestra where harmonies of strings and percussion spring from solid stone. For decades, the pillars have been the subject of scientific studies and have captured human imagination. Yet, they remain an enigma, their construction leaving scholars stumped to this day.

Courtesy: bbc