Monitoring Desk

A mother wakes at dawn to copy out worksheets for her children on to pieces of paper.

Secondary school pupils attempt to write essays on their mobile phones, while younger children queue to wait their turn on the one computer in the house.

That, according to the Child Poverty Action Group, was the reality of remote learning in some homes in the first UK lockdown in March 2020.

“We spoke to thousands of parents, carers and children and the thing we heard was that up to 40% of them did not only not have access to a laptop or the internet, but also to other things like printers, even stationery and craft materials,” said Kate Anstey, a project lead at the charity.

Now, as we enter another lockdown that could last until the February half-term or beyond, the government wants even more online learning – with schools mandated to provide at least three hours per day and Education Secretary Gavin Williamson calling on parents to report schools who are not providing enough resources.

Government help ‘not enough’

It is estimated that 2.6 million schoolchildren live below the poverty line in England alone, and Ofcom estimates that about 9% of children in the UK – between 1.1 million and 1.8 million – do not have access to a laptop, desktop or tablet at home. More than 880,000 children live in a household with only a mobile internet connection.

Businesses and charities are helping out. The London Grid for Learning (LGfL) has a scheme called Bridge the Divide, which is leading a nationwide procurement scheme for two million cheap Chromebooks and WinBooks.

And to help those without devices, the government has sent out more than half a million laptops to the schools in most need.

But the government help “isn’t going far enough,” thinks Ms Anstey, and even when laptops are arriving, the problems aren’t over.

“We have heard from schools that have had laptops, but they have arrived without the right software,” she said.

To help parents struggling to afford data, EE, O2, Three and Vodafone are planning free access to the Oak National Academy online lessons, so that families can continue to learn from home without using any of their mobile data allowance until the end of the academic year. The networks are completing their technical tests over the coming weeks before rolling it out.

Tips for parents from experts

- Do what you can. You don’t have to become a teacher. You are a parent and what your child needs most is what parents give best – love and support.

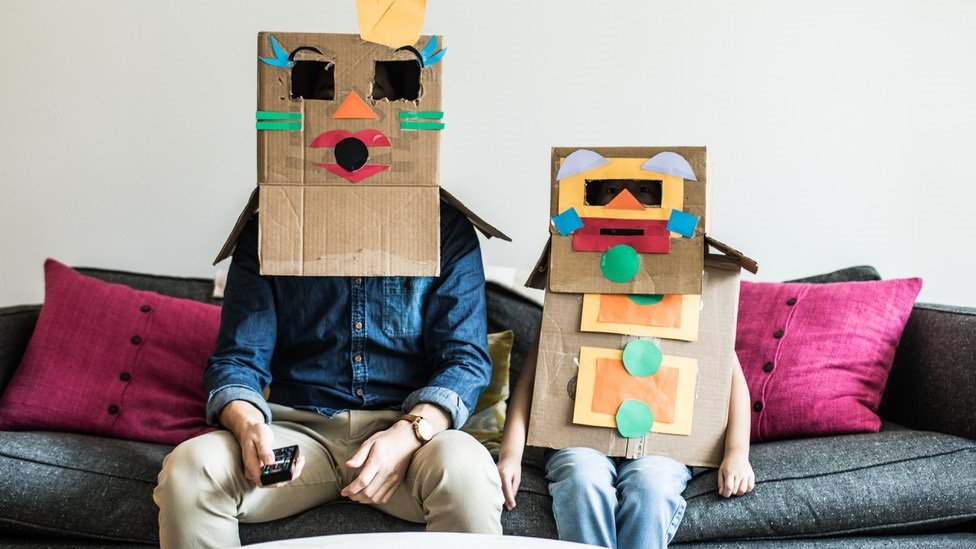

- Provide a structure to the day – this does not need to be a strict timetable. And for younger children, keep the afternoons free for more fun activities, craft, cooking, PE.

- If you can, set up a small workstation for your child. Headphones could help for online lessons.

- If you have a Playstation or Xbox, but not an extra computer, both Microsoft Teams and Google Classroom can be accessed via the consoles.

- Talking and reading don’t need devices – and both are vital skills.

- Practise the basics, like multiplication tables, playing with money, or imaginative role-play.

Matt Lawson lives in Cumbria and has four children of school age. His broadband and mobile signal is so bad that he has to rely on the schools his children attend sending work by post. For his daughter, studying for GCSEs it is particularly hard.

“She was also involved in a lot of clubs which are carrying on on Zoom so she can’t join in. It is ridiculous.”

Some schools are ahead of the game because they embraced the digital curriculum before the pandemic.

Phil Hedger is chief executive of the LEO Academy Trust, a group of six schools in the London Borough of Sutton. Back in 2018, it decided to provide every child with a Chromebook, and in lockdown has found children have thrived because they were used to the technology.

“What works online is high-quality short bursts of teacher-led learning for 15 or 20 minutes, and then offline activities,” he said.

Not all lessons the school provides are live. Some are pre-recorded and there is a plethora of excellent resources already online from places such as BBC Bitesize for teachers to draw on. One Monday, the BBC is also launching curriculum-based programmes for primary and secondary school children, on terrestrial TV channels CBBC and BBC Two.

If teachers do provide live lessons, they stay online afterwards to help children who are struggling.

And children know the etiquette of video conferencing, including how to mute themselves and even setting up their own meetings to support their peers. For children without access to the internet, the school provides dongles for a mobile connection.

Jonty Clark is chief executive of the Beckmead Trust, which caters for 400 vulnerable children with complex needs.

He took matters into his own hands and secured funding from two charities to supply laptops and dongles to both their own and partner schools at the beginning of the first lockdown.

It paid dividends. Some of the older children were “already involved with the justice system”, he said, and having laptops has kept them off the streets and stopped them offending.

And for some children, such as those with autism, working at home on a laptop has seen them “flourish” academically.

Courtesy: BBC