Nick Bryant

SYDNEY : The Sydney Opera House recently commemorated its 50th anniversary. The iconic design is one associated with the Australian city the world over, along with the steel arch bridge, which spans the harbour. Considered a triumph of 20th Century architecture, it very nearly didn’t get built in the international search to find a design.

This vision of modern beauty, with its famous curves covered in more than a million bright white ceramic tiles, was initially placed in the reject pile. But its journey to realisation says much about Australia today, according to Sydney-based correspondent Nick Bryant.

“From sea level on the harbour, its giant shells look like billowing spinnakers. From directly across the water, they remind me of the bonnets of nuns. In profile they’ve been likened to oyster shells, while from the nearby botanical gardens, they resemble the unhatched eggs of some giant prehistoric beast. Still, I can pinpoint the precise moment when it first caught my gaze.

I was driving back from another of Sydney’s great icons Bondi Beach, and I’d just turned the corner on one of the roads that takes you back into the city. On the horizon, I could see the steel girders of the Harbour Bridge, ‘The Coathanger’, as it’s known here, and then its partner in one of the world’s great structural double acts. Even as a kid I was transfixed. I wanted to be an architect. This was the course I started studying at university. Through poring over architecture books, I have fallen in love with Jørn Utzon’s masterpiecelong before stepping foot in Australia. I’d always looked upon it as the 20th Century’s most superlative buildings.

What I have failed to appreciate before coming to live here was how the Opera House was also a structure of such multiple meanings, and how it encapsulates the contradictions of the nation it has come to symbolise. The country’s most instantly recognisable building is a landmark to Australian ambiguity. The most obvious interpretation is that it represents Australia’s rising post-war self-confidence. The appointment of Jørn Utzon, a little-known Danish architect without a major project to his name, was a sign of a less insular outlook and a new spirit of national assertiveness.

Jørn Utzon was a little-known Danish architect without a major project to his name (Credit: J. R. T. Richardson/Fox Photos/Getty Images)

This internationalism was evident too, in the global competition that attracted more than 200 entries from all around the world, and also in the role played by its most influential judge, the Finnish American architect Eero Saarinen, who plucked the Dane’s revolutionary design from the pile of rejects and thought he’d found the rightful winner.

But there’s also a tragic backstory of how, when delays and cost blowouts put the entire project in jeopardy, Utzon was replaced by a local architect, and how the spellbinding interior that’s an envisaged never became a reality. Whereas the Dane was obsessed with form, Peter Hall, the head of the government team that replaced him, was preoccupied with function. The interior then is anti-climactic. Utzon’s forced resignation showed that a dreary provincialism was still hard to shake. The Dane never returned to Australia, thinking his opus had been disfigured.

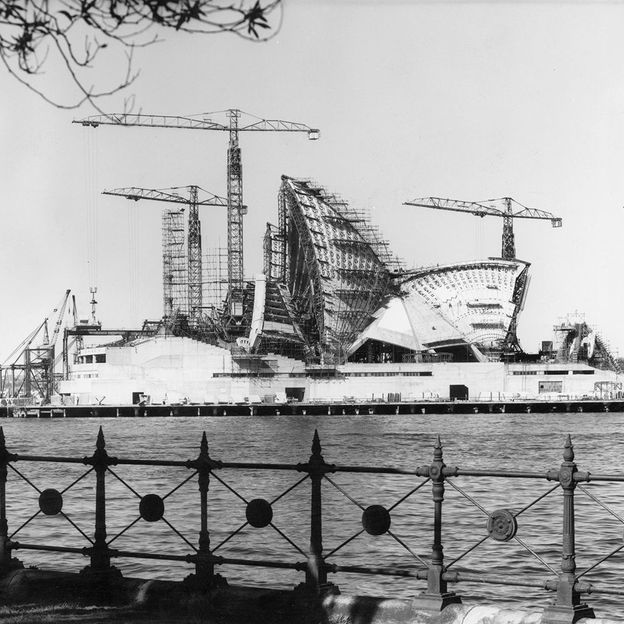

So many strands of the Australian story come together in this building. New immigrants from southern Europe provided much of the manpower for its construction, which speaks of Australia’s post-war multiculturalism. In November 1960, Paul Robeson, the Black American opera singer, even performed an impromptu concert amidst its scaffolding and cranes – his sonorous Old Man River, a musical foreshadowing of the end of the White Australia policy, which for decades that limited non-European migration here. [The Opera House] was opened by British woman, Queen Elizabeth II, but in a ceremony that included Indigenous ritual in recognition of First Nations peoples. It occupies an outcrop in the harbour named Bennelong Point, which was named after the elder from the Eora Nation who served as an interlocutor with the British in the 1790s. In an expression of cultural egalitarianism, the building’s opening celebrations in 1973 not only featured Wagner but also a populist counterpoint: Rolf Harris singing Tie Me Kangaroo Down Sport.

After the ‘Black Summer’ bushfires of 2020, the tired faces of firefighters who had battled the flames were projected onto it (Credit: Brook Mitchell/Getty Image)

The opera house probably would never have been built had it not been financed by lottery money, reflecting the centrality of gambling in Australian life. Advances in projection technology have turned its shells into a giant national billboard. Poppies are projected onto it on Anzac Day, when Australia remembers its war dead. After the ‘Black Summer’ bushfires of 2020, it was the tired faces of firefighters who had battled the flames. It has become a focal point of national celebration and of protest. Only [last] month, pro-Palestinian protesters converged on the building, some shouting antisemitic chants after its shells were floodlit in the colours of the Israeli flag in sympathy with the victims of the October 7 attacks.

But the reason why the Opera House has become such a fitting Australian landmark is that it’s unfinished and incomplete. Moreover, most Australians think it’s great already, and not in need of further improvement, which makes it doubly emblematic. That its golden jubilee should coincide with [the recent] referendum in which Australia said ‘no’ to the creation of what was called an Indigenous voice to Parliament feels fittingly synchronous. As with the Opera House, so with the nation: do you see an Australia already glorious and complete, or a confounding country not yet fully realised?”

Courtesy: BBC